interview

Marta, I’d like to know why you began this series towards the end of the 1970s. Just when the great boom in painting began globally, you turn your back on painting. You had done your last exhibition in the U.S after a series of amazing happenings and performances, most of them took place in New York, and then after that you did your erotic paintings, Frozen Sex, and then you return to Argentina.

to enlarge

Retrato Minujín en su taller en Washington DC, Estados Unidos, con la serie Frozen Sex, 1973.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

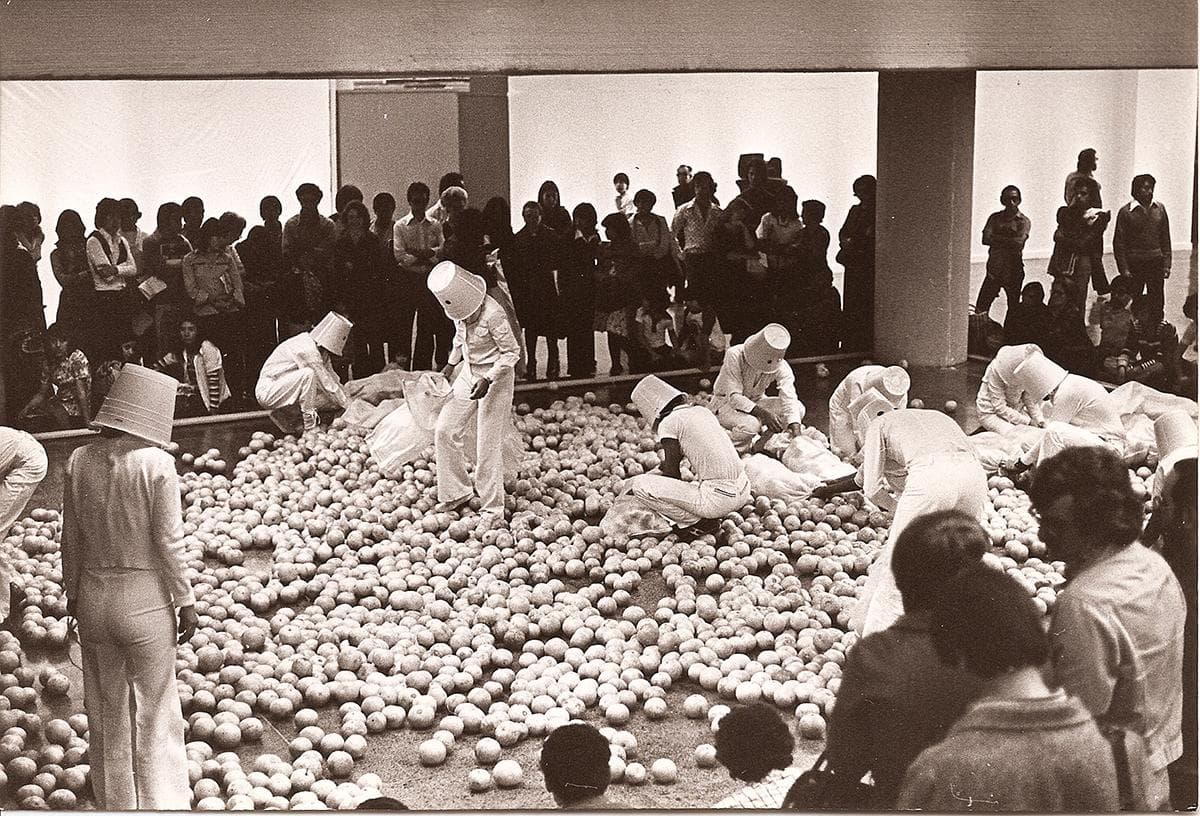

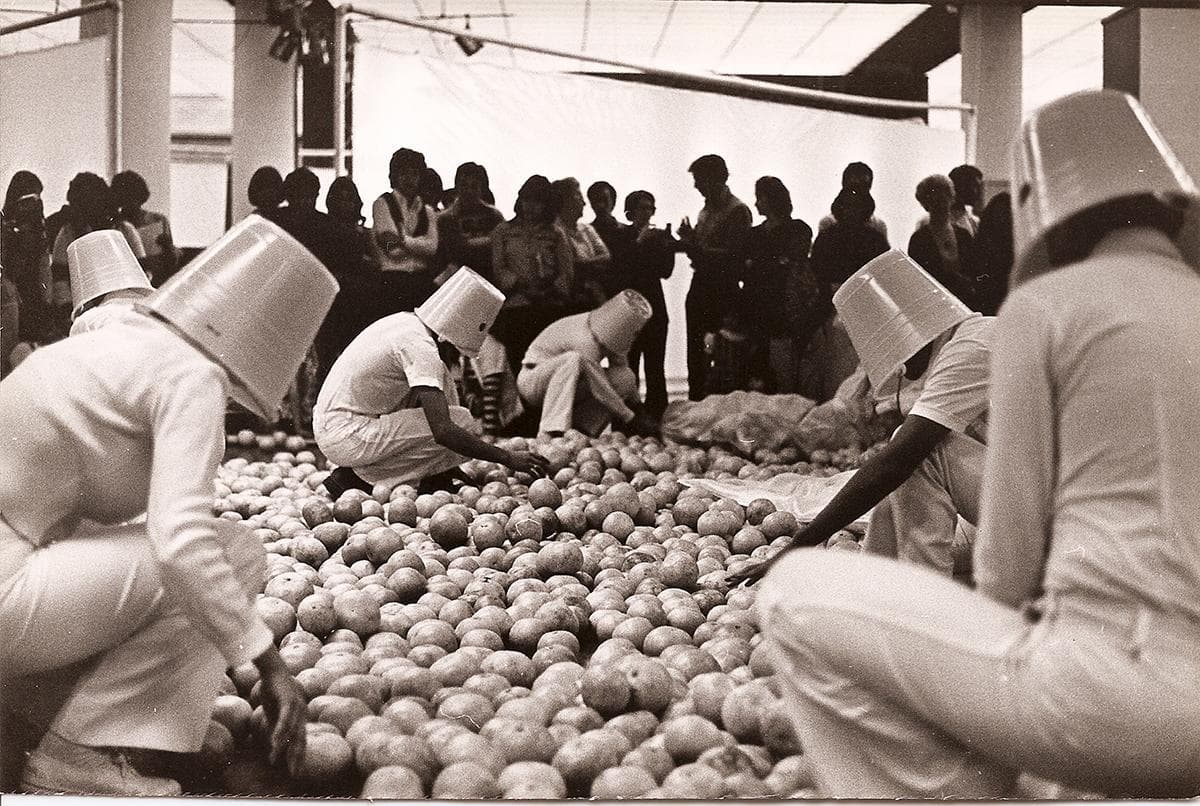

Before, it was before that, in ’72, ’73, during the erotic series. That’s why I did it, because I was in Washington, it wasn’t really an important event in my life. I was in Washington, I hated Washington. I was there, and I was simultaneously doing all those performances that I did in the Museum Of Modern Art and at the Soft Gallery in Washington, and after that Interpenning, which I did with Juan Downey.So, I was already doing performances, and very intense ones at that. But when I arrived here, I don’t know what happened, but the first thing I did was the thing with the grapefruits in Mexico, in ’77.

to enlarge

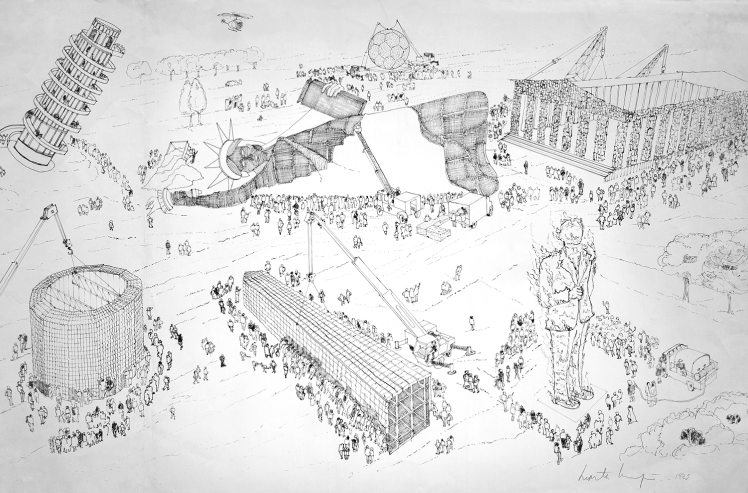

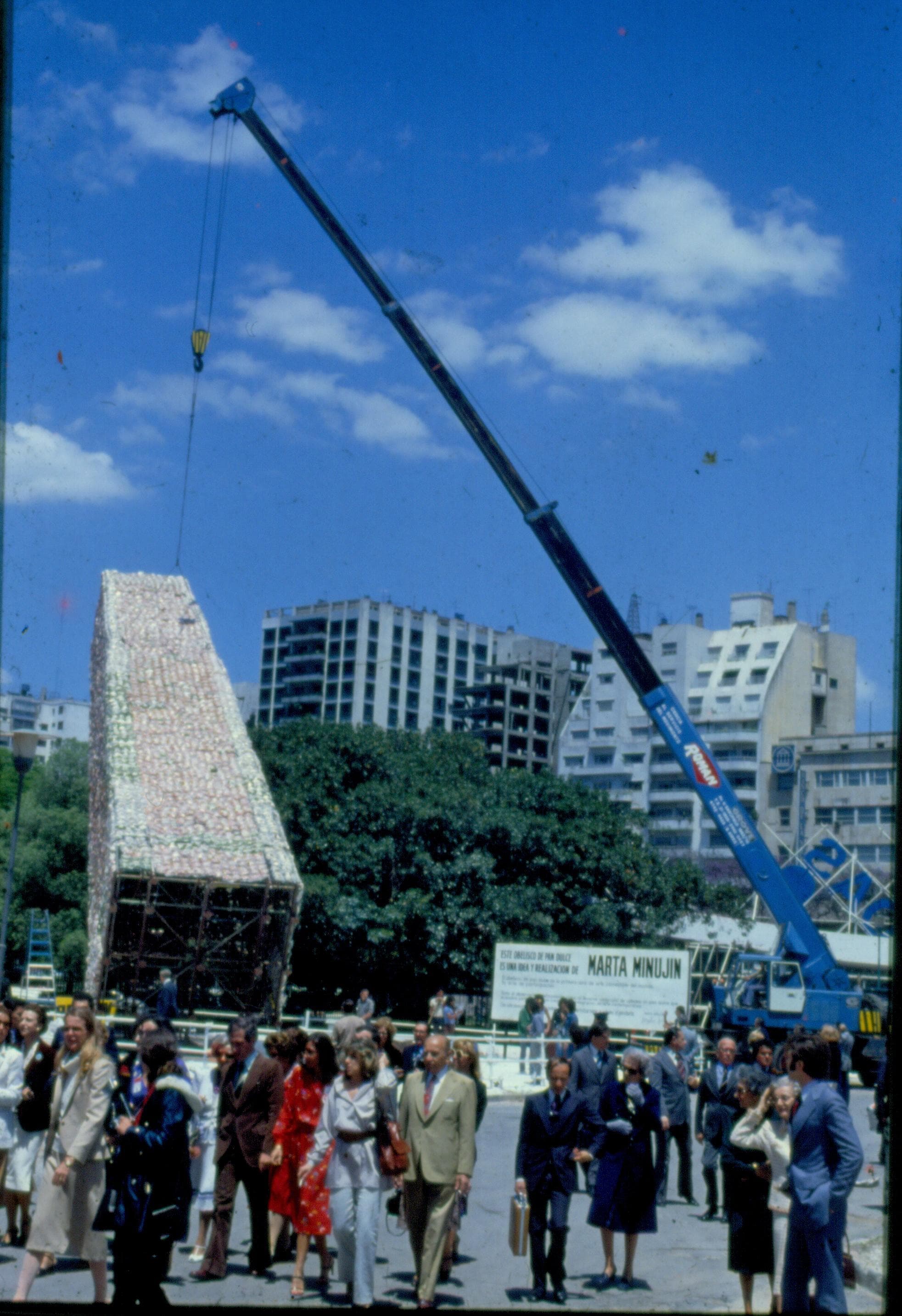

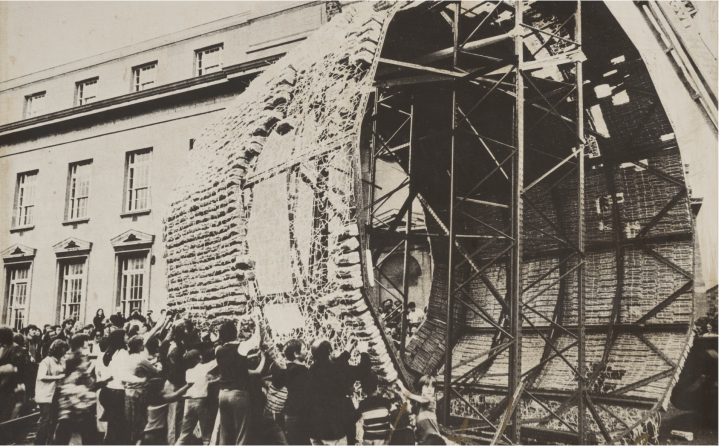

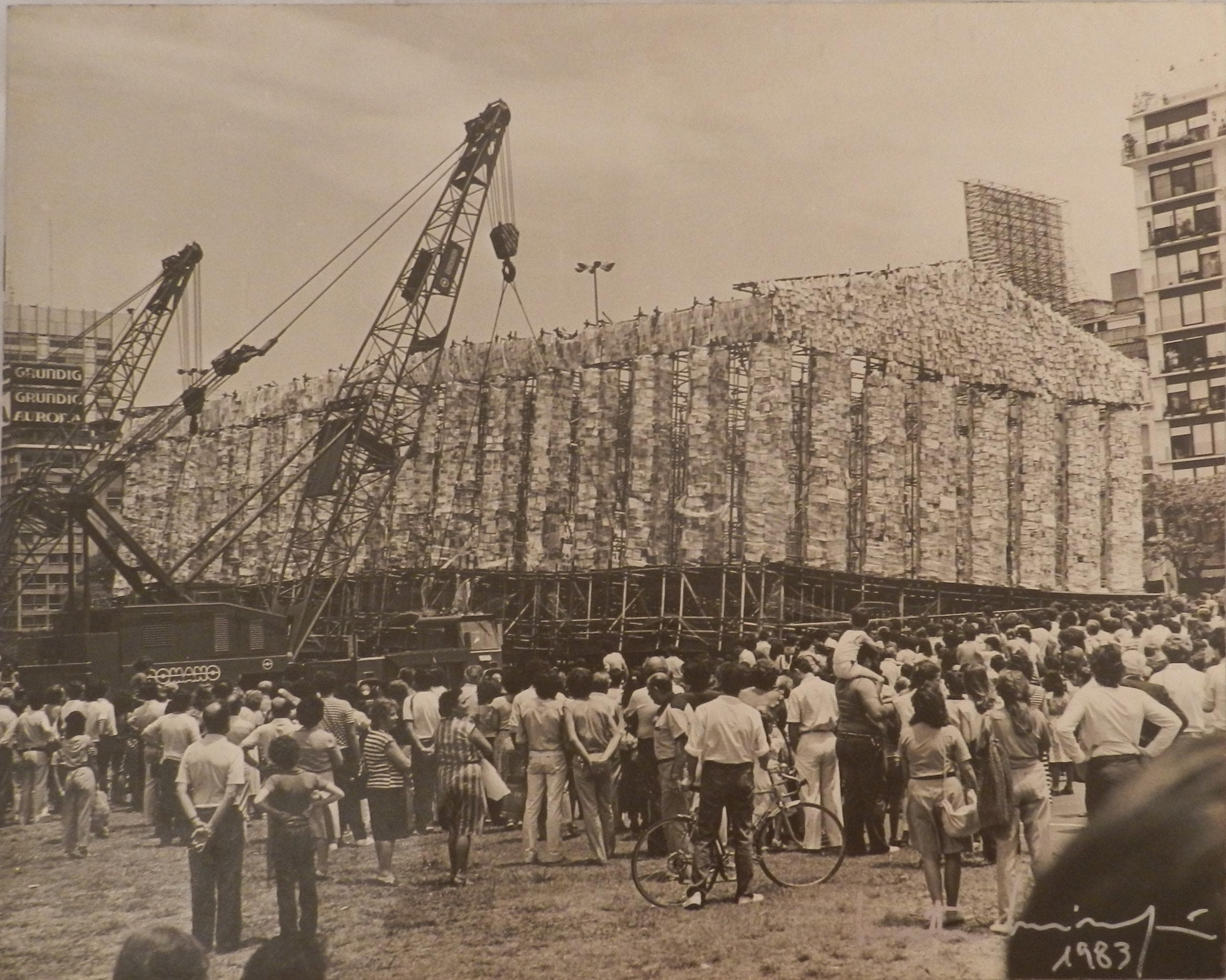

Sure, but the series of Fallen Monuments kicked off in ’78, starting with the Obelisco Acostado (The Obelisk Lying Down) that you did for the first, and only Latin American Biennial that took place in São Paolo . After that you did the Obelisco de Pan Dulce (The Obelisk of Pan Dulce). And you carried on the series from there. What was it that made you want to step back into that universe, organising huge events? Because I don’t see them simply as an intervention to monuments, what you have is a combination of sculpture and also the happening and the performance.

Bienal Latino-American, Parque de

Ibirapuera, São Paulo, Brazil.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

Yes, all of that’s true. When I arrived in Argentina when I came back, in ’75 I think it was, I did the Academia de fracaso .

At the CAYC (Centro de Arte y Comunicación), right?

Yes, at the CAYC. The military were winding me up so much, they started in ’76, and the perpendicularity of the obelisk, I just had to lie it down on its side. It was a bit like, I had done a bit of erotic art and it was like the penis lying down, the penis overthrown. That’s how it started. Taking a monument that had always been vertical, and then with the soldiers, it ends up lying down, it falls down. That’s what happened. And after that I made the obelisk fly…

It wasn’t only lying down, but in fact you could actually penetrate it.

Sure, at the São Paolo Biennal, you went inside. I climbed up the real obelisk and made a film from the top, and the idea was that you were flying, you pass over it. The film was shown inside the obelisk which was lying down, with a path inside, half the length of the obelisk. Big Ben will also have a walk way and film inside it.

And then the following year you did the Obelisco de pan dulce in Buenos Aires, in ’79.

to enlarge

Well, it occurred to me that not only could you lie them down, but you could also eat them. And since pan dulce is such an important thing here in Argentina at Christmas, it was also a way of gifting people the 30,000 pan dulces, that were given to me by the owner of the pan dulce factory. And he funded the whole obelisk. And then there came the dance between the obelisk and the crane, lifting it up, lowering it back down, lifting it and lowering it. Then what happened was almost like an act of violence because when we lay it down on its side, fifty thousand people threw themselves on the obelisk and the firemen had to spray them with water to disperse them, it was like a plague of locusts. And they all took away pan dulces. So I saw how this intense participation of people could really achieve something, with something so simple…it was just an obelisk of pan dulces.

to enlarge

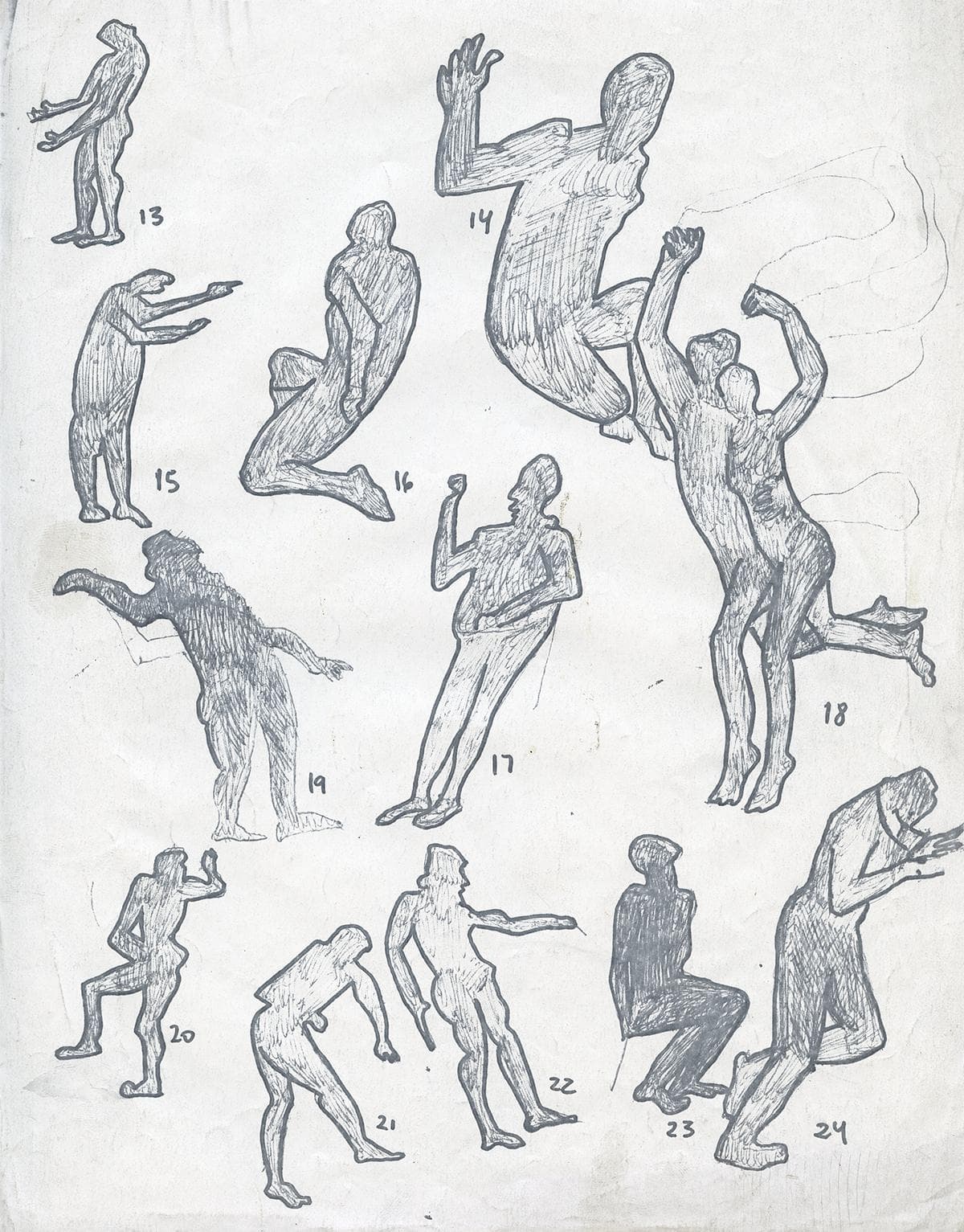

I find it really interesting how you talk about this ‘swarming of the collective, the masses’, which you used once again when you did the Suceso Plástico (Plastic Happening).

That’s right, and the Menesunda (Mayhem) too, which I did in my hometown.

That was different, because the Menesunda (a labyrinth-type of structure) doesn’t have the collective component that the Suceso Plástico did, which occurred at a stadium where a helicopter scattered foods to the audience.

Exactly, they threw living chickens down on them. It was an incredible thing, so many things happened to the spectators. It was a happening that was almost half-violent and after that I stopped, because I didn’t want to do any more of that crazy stuff as they said someone could die or have some sort of attack, that sort of thing. Because it was all just crazy. In those eight minutes everything happened, chickens fell from the sky, there were women kissing men, there were musclemen lifting women up, motorbikes spinning around, really fat women rolling around on the floor, couples wrapping each other in tape, and I got there and I threw talc, or flour, I can’t remember which it was…

And Flour…

…And lettuce and chicken, because I was very influenced by, I’d been to see 8 ½ by Fellini when I was in Paris, and I loved all of those voluptuous women, and the lettuce and all those things that Fellini did.

I’m struck by the fact that you’re interested in this ‘swarming’ of spectators. What is your spectator like? Because you’re somebody who is very individualistic, but you always work with groups of humans. It’s paradoxical. You don’t work with individuals, you always work with organised groups of humans. In some works, especially from the 1960s, groups of participants were organised by hair colour, eye colour, social class, discipline, work, affinities, etc.

to enlarge

I see them as an essential element in my works, because suppose I’ve made that obelisk with 30,000 pan dulces. Who’s going to dismantle it? And I love that everyone takes a pan dulce back home with them and that the work ends in that way. Because I see the audience as such an important element in my work. Without the audience, the work wouldn’t exist. Without these crowds. I can’t imagine doing a huge work and then afterwards dismantling it myself. That would be completely absurd. To put book after book after book and then keep all of the books for myself afterwards. No, there would be no logic in that.

There’s a very interesting logic in what you’re saying, and you used the word ‘desarmar’ (to dismantle), which is a verb. All of your works are dismantled, except for the paintings, which you destroyed, except for the few that have survived.

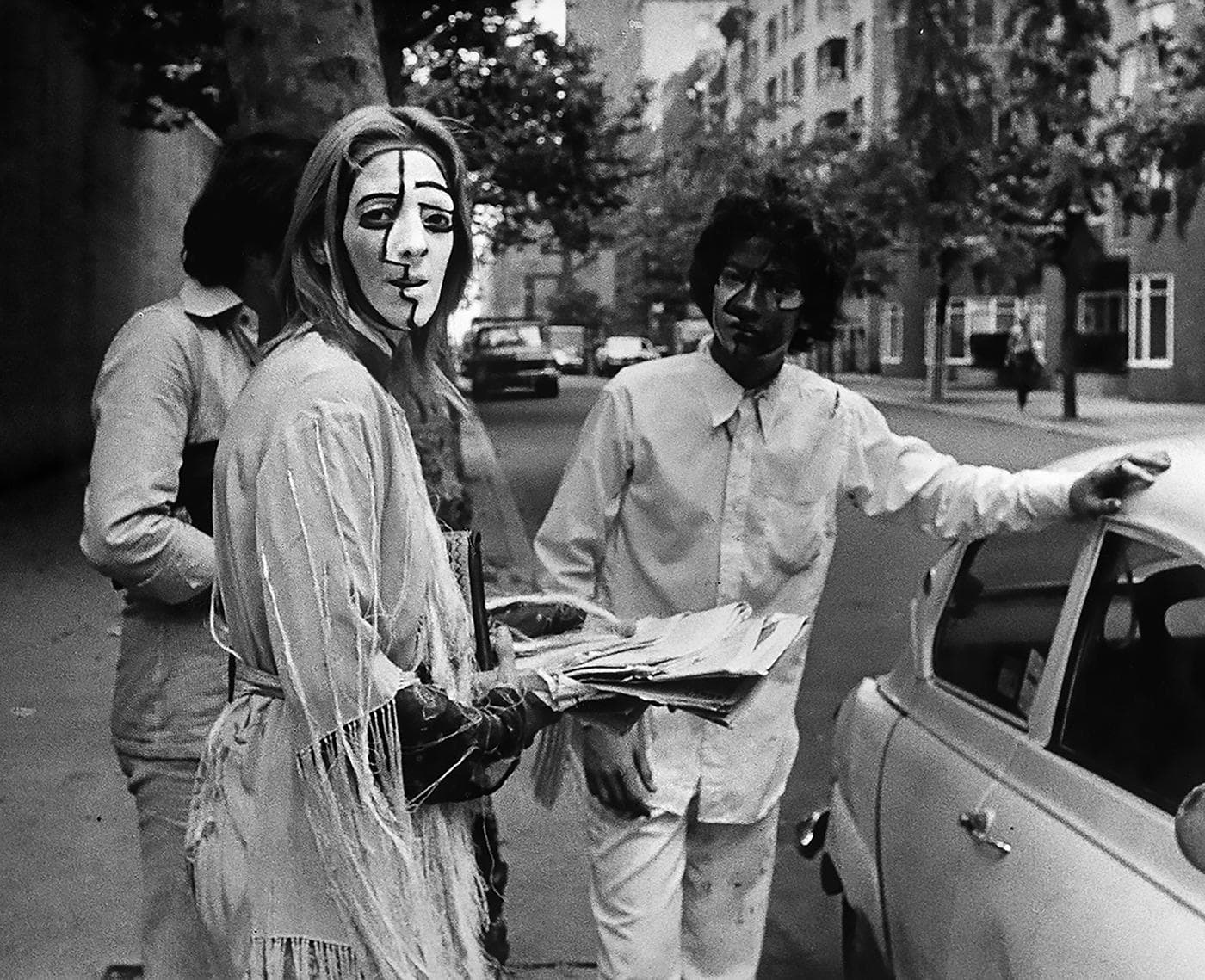

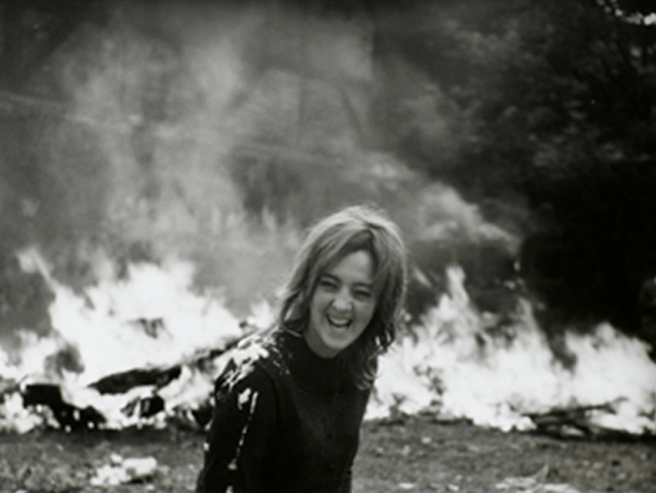

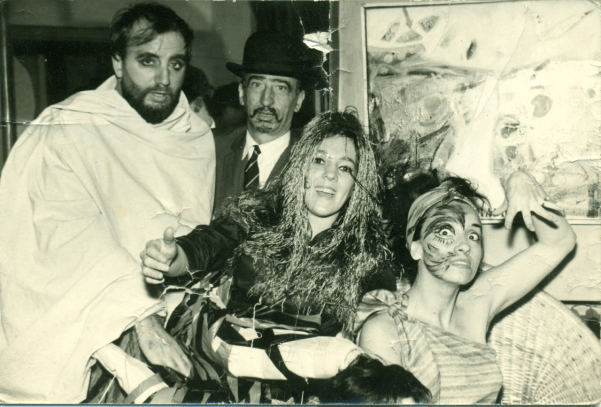

Remember in Paris for La Destrucción (1963) I got hold of eight artists to paint over my works, destroying them and making them into their own works, and then afterwards I took a flaming torch to them and set light to them. I was always interested in putting other artists in a violent situation, destroying my work, and on top of that making it their own. That’s why I’m also interested in seeing how people react.

Impasse Ronsin, París, France.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

Critic Aldo Pellegrini talked about the liberation of energy in your work dealing with destruction. He considered destruction as a creative freedom. Do you see it in this way?

Well the destruction in itself, yes, but the destruction created a brutal energy, because we released birds up into the sky, and the fire, and the firemen came. The firemen always came. And they would put out the fire, and then throw us all out. A hit of brutal energy. In reality it was like they were living in a comic strip, in Paris, the first time I did that. But I’m always interested in the audience, that’s why I was so interested in La Menesunda, why I let each person in one at a time, into each space, to see their reaction… like art that has to be for everyone.

to enlarge

to enlarge

La Menesunda is a piece that is very sui generis because individualities come into it, while the other pieces are pieces of crowds or larger groups.

Anonymous, anonymous, yes.

Yes, the audience is drawn to it, because in some way they recognise a monument. What was it that determined your choice of monuments? Was it to do with them being loved by the people, or with the story of that city?

No, no. As the third millennium approached, I was interested in why we still have the same universal myths, that people flock to, like here the obelisk is the centre of Buenos Aires, like the Arc de Triomphe is the centre of Paris, or the Eiffel Tower… These places that people have charged with their own energy. But they were really ancient myths, and so I wanted to make them new. And to make them new, it occurred to me that, as the world we were heading into was multi-faceted and multi-directional, where things are seen from different points of view - diagonality and action-relativity, everything seen from different points of view - that’s what interested me. To recreate, that all the people who looked at the obelisk make their own monument connected with the moment they were living in. That was my ideal, that people would make new centres in the cities.

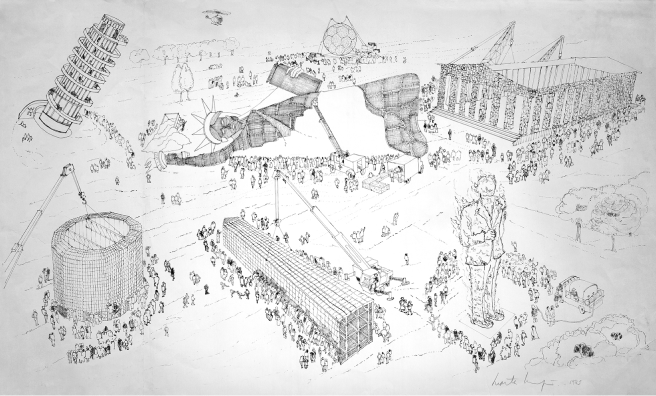

Ok, but there are several things are combined here. You’ve got the monuments, which we could say are classical , because an obelisk is four thousand years old and then you’ve got the Temple of Efeso, and also the Parthenon, which come from the civilization of Greek culture. But there are also characters, which aren’t monuments. There’s James Joyce, the writer, Carlos Gardel. Then there’s a another element which is Pop. For example, the football (that you haven’t yet realised), the sea lion, the emblem of Mar del Plata, which is a charismatic animal, and there’s also the Tower of Babel.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

And the Statue of Liberty – that’s also Pop.

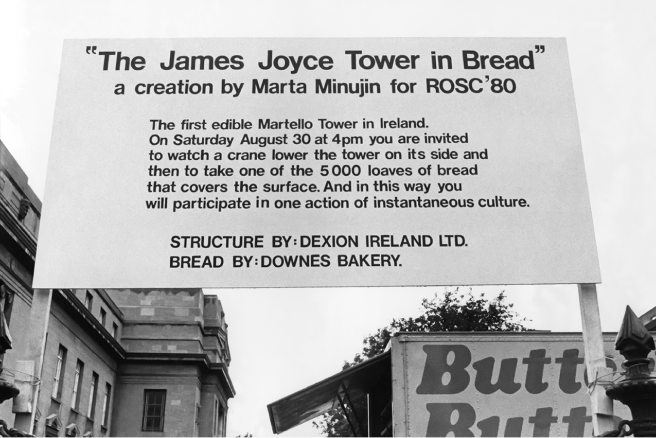

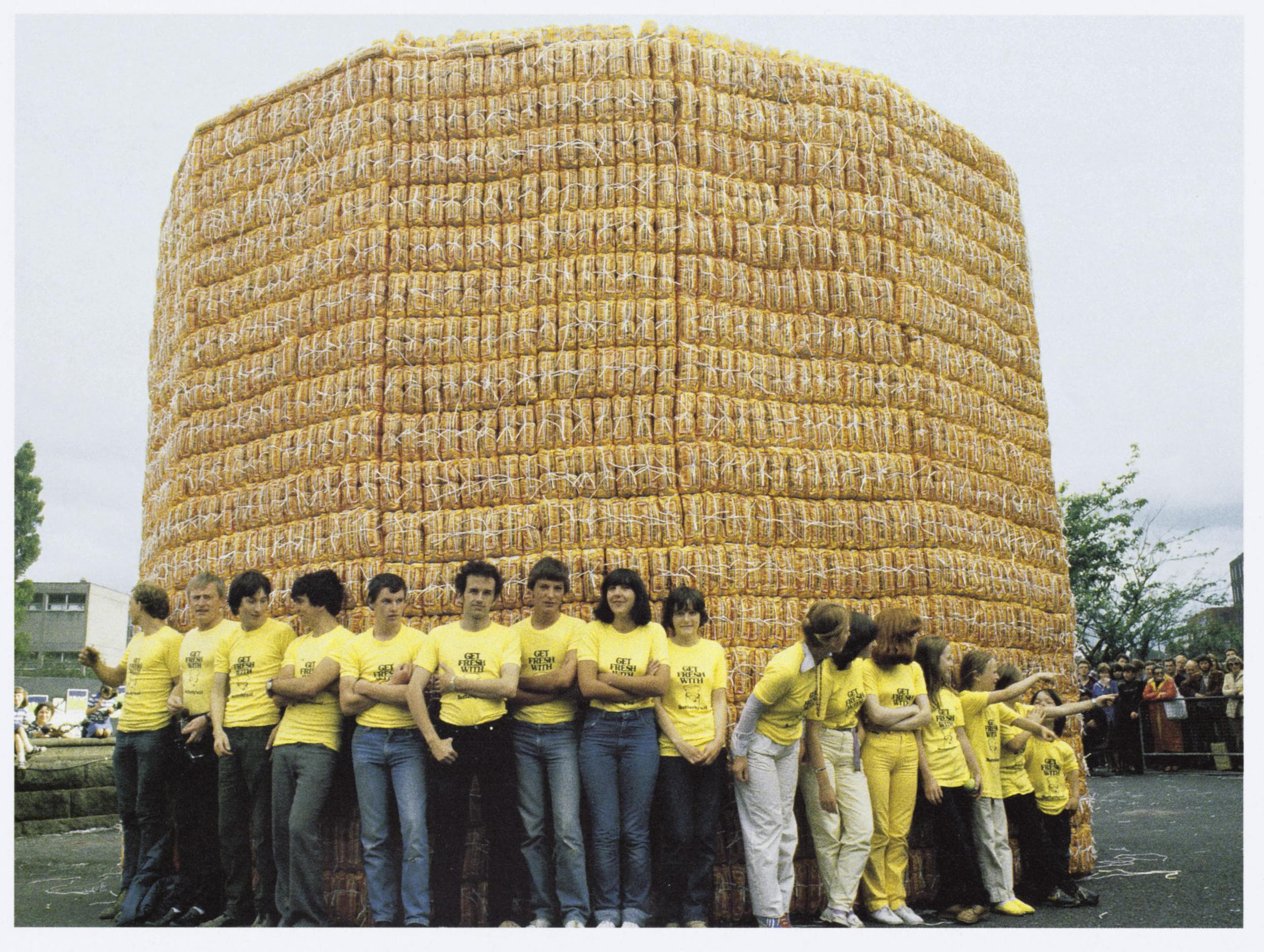

Yes, yes, but they’re monuments that exist. So, there are several layers of meaning, it’s not just the physical monuments. You also combine the literary world, because the third work you did, in 1980, which also took place in the United Kingdom, in Ireland, in the fourth ROSC exhibition, was the James Joyce Tower of Bread .

No, no. The museum of James Joyce is in a Martello tower, the structure exists – there are 29 towers in that area. To defend themselves from Napoleon they made the Martello Towers, and the James Joyce Museum is a myth in the city of Dublin. And I made it with bread because there’s a story by James Joyce that talks about a baker, and I went to Ireland on a plane, and I thought “I’m going to use the baker who James Joyce names,” and in the end I found him and he funded the project. Don’t forget I also have to find people to fund these works. I never do anything for money, but the works are made, they’re like miracles.

Dublin, Ireland. Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

Well it’s like an architect with a building. You make a building and then you demolish it. A work that’s dismantled, a work where nothing remains except for the documentation, an ephemeral work. So let’s talk about the ephemeral. You have two things – on the one hand the monument, that you recreate because you make it with structures as though it were a building. It’s a structure that you build. And on the other hand, you destroy it, and destroying it generates a ritual, a ritual related to food or knowledge, to sharing or giving away, generally.

And to the audience, that’s fundamental. Related to people.

to enlarge

Dublin, Ireland. Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

In the case of Carlos Gardel, which we’re going to talk about later, that’s a very important piece. In that case you burn it, but generally you use food.

And books now. Now it’s all books, books, books.

Sure, the so-called food of the soul which is books, right? They say they’re food for the soul.

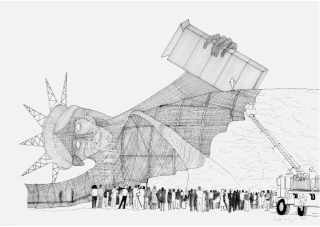

Let’s focus on the Monument series – El obelisco acostado, El obelisco de pan dulce, James Joyce Tower of Bread, El Carlos Gardel de fuego, El partenón de libros (The Parthenon of Books). Then between ’79 and ’83, a series of projects that have not yet come to fruition including the Statue of Liberty, several versions of the Leaning Tower of Pisa - there’s one made of rubber-soled shoes, another made of bottles - that had to do with the funding, the football that you had drawings for but never completed, the one made of dulce de leche, the Eiffel Tower made of baguettes Torre Eiffel de pan baguette ), the Berlin Wall made of sausages and the Pan de azúcar de Feijão , which you were also going to set fire to.

Yes, yes.

Then later in 2011 to 2018 you did the Torre de Babel (the Babel Tower), the Ágora de la paz , the Lobo marino (The Sea Lion) and the Partenón de libros . Those were two moments with real impetus - the ’80s, then you stop in the 90s, and you start the happenings again in 2011. So let’s talk about them one by one so…

Yes the Torre de Pan.

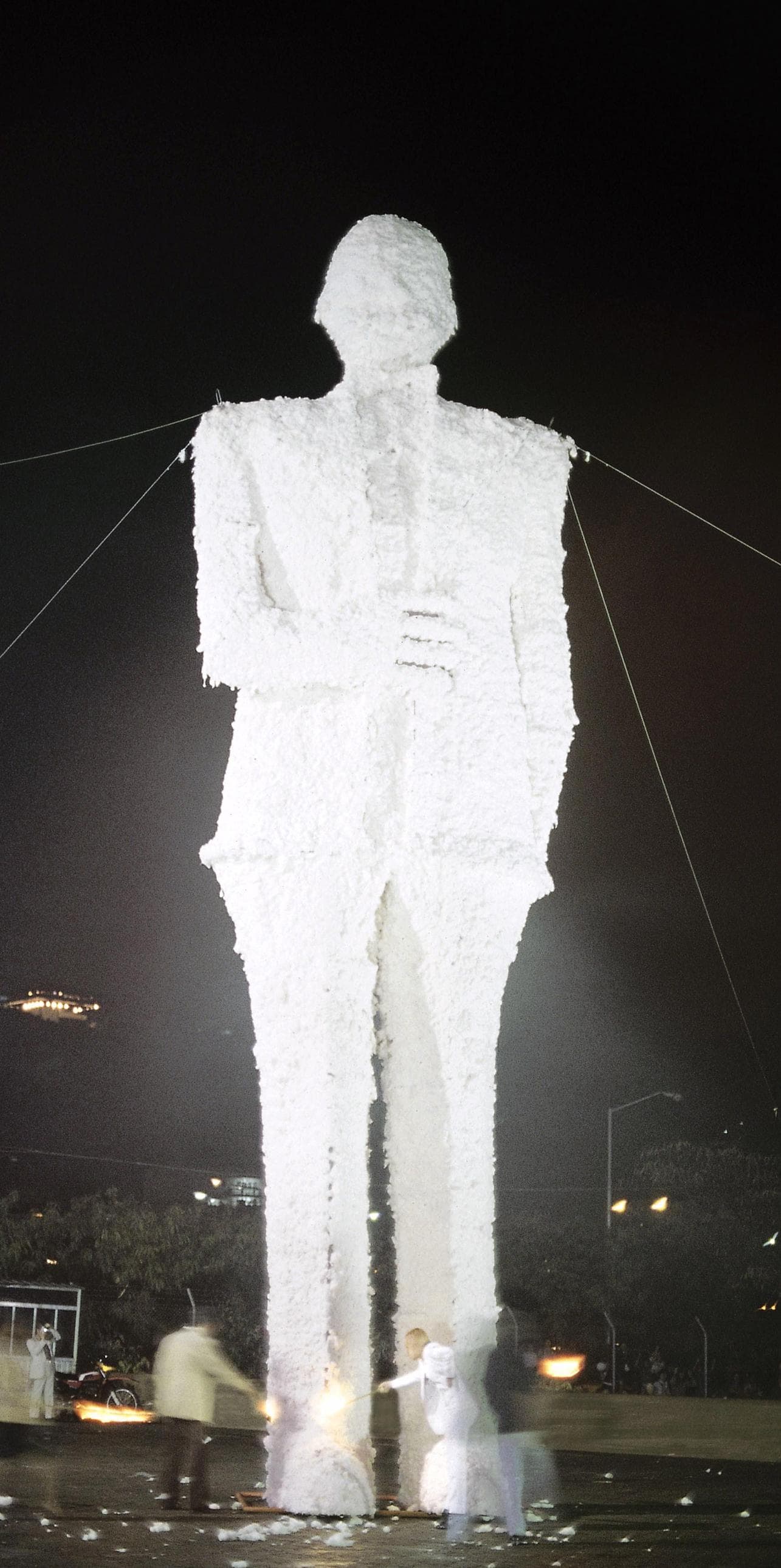

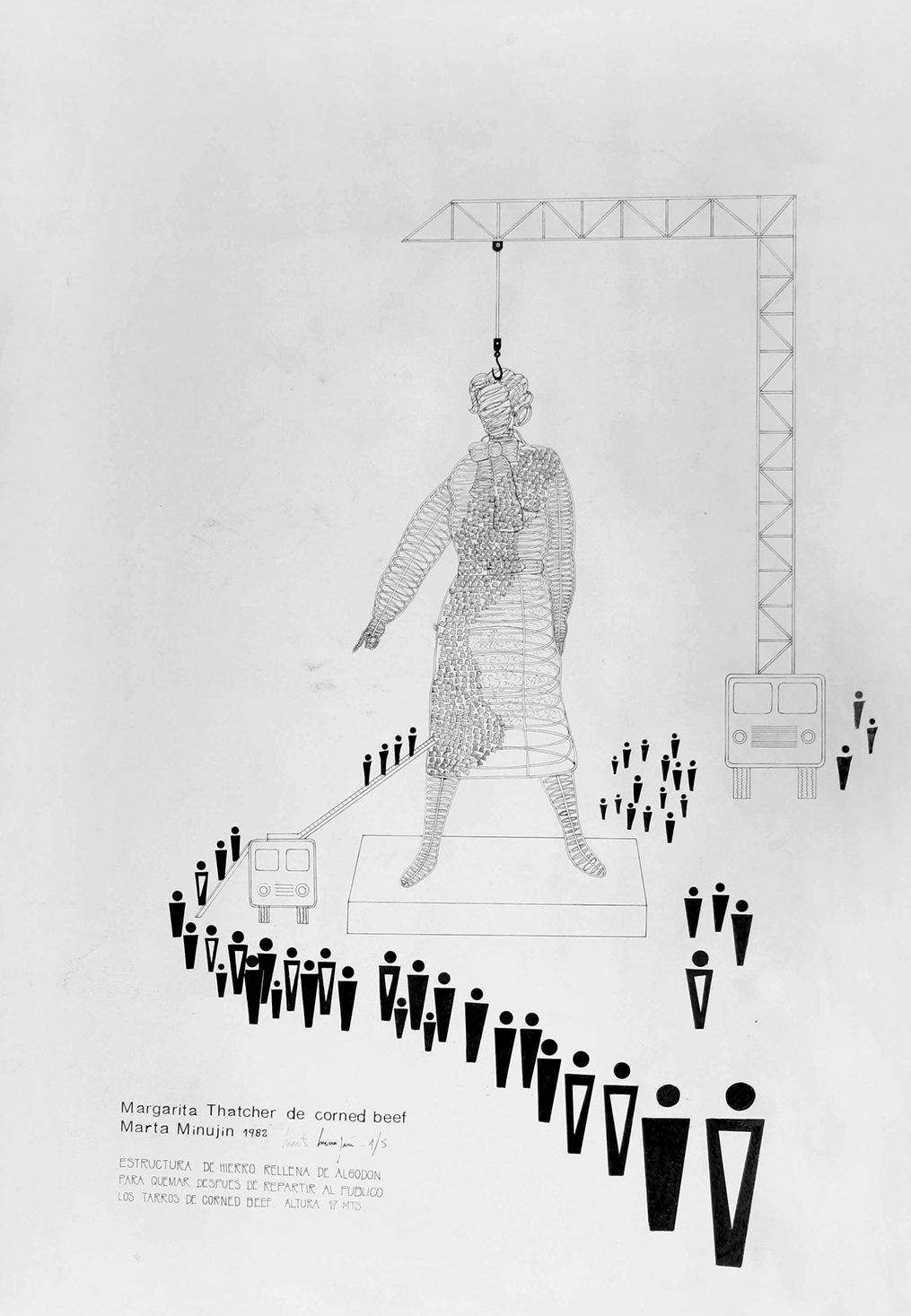

And the next thing you did, in ‘81 at the Third Biennial of Medellín in Colombia, was El Carlos Gardel de fuego .

Well I’ll explain it to you – it was like this. They invited me to the Biennial, and Ana Mendieta and Carl Andre were there, and the genius that was Leonel Estrada. So I was invited, and it occurred to me that since Gardel died in a fire, an accident in Medellín… I went to the Casa Gardeliana - everyone there loved Gardel, there was a whole neighbourhood where everyone was dressed as Gardel, and that’s where I got the funding. I managed to get hold of bundles of cotton, because Colombia is a country that exports cotton. And the idea was to create a Carlos Gardel 17 metres tall, wrap it with cotton and set fire to it. It was like an homage to Carlos Gardel. But that too was ephemeral. And it was so interesting because the people went up to the fire, they almost burned themselves, I almost burnt myself, and it was so high and the cotton fell down on top of them… and the people went crazy, crying, and they started singing Gardel’s songs. It was really moving, yes.

to enlarge

Carlos Gardel is another figure that you’ve chosen that has something that is very attractive to people, that appeals to people’s affective structures.

Yes, to their emotions.

People identify with these figures. But it’s not only the local audience that identifies with these figures, but also tourists.

That’s right, and there’s no monument for Gardel, but tourists do still gather here at the Chacarita Cemetery where he is buried. Yes, that was a huge monument, and then later I made another enormous one of Margaret Thatcher, again a person…but not for good, for bad.

Very different!

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

Let me go back to something you said. You said you wanted to displace the myth of one country to another. What is a myth to you? Is it a story?

No, no. To relocate a myth, no, no - it’s an emblematic figure that people identify with, but it’s also mythical. If people encounter the obelisk, if they encounter the Eiffel Tower, encounter Big Ben in London, it’s something where they all hypnotically follow a path, a course that has been created over many centuries that have gone before. So that place interests me because so many people go there, so that’s where I produce that change, and that could be an ideological change. And in seeing it lying down, it changes everything for people, it’s prophetic.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Studio.

You talk about an oblique state of consciousness. And you’ve also said that you wanted to change the world’s laws of gravity.

Exactly, because it has to do with the fact that everything must be perpendicular. If all the buildings are perpendicular rather than at an angle, you create perpendicular thinking. So I wanted to mobilise this thinking in all directions. One direction is to lie it down. Make it oblique.

Do you see these undertakings into what you call myth - where you mix icons, commemorative monuments, communities, and public figures too - do you see them as universal? Do you think everyone reads them in the same way?

Yes, definitely, because all the tourists who are coming out of this pandemic, creating incredible worldwide masses, are always going to look for some sort of reference and they’re always going to see something like the Great Wall of China... The Great Wall of China has so many refences, if I lie it all down, which is impossible, but if I lie it all down… Before, people used to go to see the Berlin Wall, and then I suggested people ate it with sausages, because the idea is to create new myths. To give everyone the space for them to invent their own myths too. And this is how it should be. In a thousand years, by that time we should have created a new sign, because what we’re living is new. For example, the pandemic is new, so if we create a huge monument to the pandemic and people encounter it, everyone who has experienced the pandemic will go there. It’s a strange thing, and that’s why I’m interested in it. That people are drawn to that thing as though they represent them. Like Egypt with the pyramids, it’s something like that. Lying down the pyramids, lying down the Sphinx

With these events, I’m not going to call it culture and nor do I want to call it a monument, but I’m blending the two things that unleash a collective energy... Is that a democratic endeavor or is it anarchic? How do you see it?

Apolitical, beyond politics. It’s something almost spiritual. I always say that art is above politics, and it’s not any kind of religion. Art is not religion, but it’s above that, like the of love…love between two people, two people who know why they fall in love has to do with this too, it’s not on a political level and it’s not on a…it’s as though it’s not real. And art, or at least what I do, I like to create this situation with people, this emphatic movement of being together in an adventure. Together, like when they dismantle my works - lots of people together who don’t know each other.

Sure, but when they’re together, and you bring down the monument, you invite people to eat, or to take books, in some way you’re breaking with the sort of a consensus and conviviality because as you’ve said, it can create violent moments when it’s shared out.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

Yes, yes. People can have terrible accidents, that’s why I take care now to make sure that doesn’t happen, because actually doing them in Europe, people there are a lot more careful, there’s more protocol. What happened in Argentina, in the football stadium, nobody was keeping an eye on that. I put the chickens in the helicopter, and nobody said anything about me throwing all that down, the fat people rolling around the floor. There could be a terrible accident but there wasn’t. There wasn’t, but it’s an art that has similarities with Christo, it’s impossible art too, that’s why it takes me so many years to fulfil a project like the Statue of Liberty, and yet there are others that I do straight away. I do them, I’m invited by cultural places, cultural spaces. They invite me and then the idea comes to me, related to that country and I start working with the myths, which to me seems like the most interesting thing that can happen now. And Christo moved incredible mountains and this has much to do with it - impossible art. I believe it’s multidirectional art, and impossible art, and when I do it a bubble crystallises where reality is broken. It’s very strange, all of it, it’s strange, but that’s how it is.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

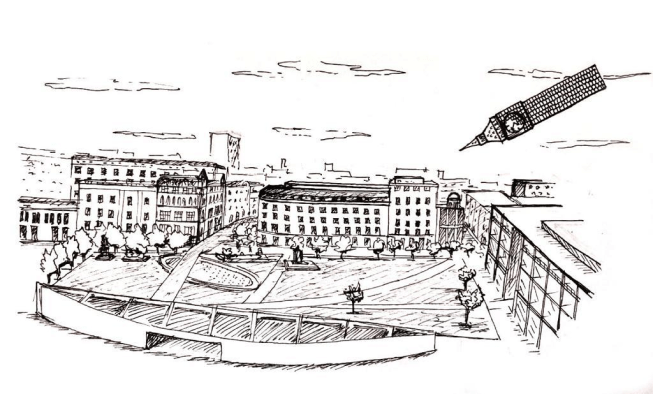

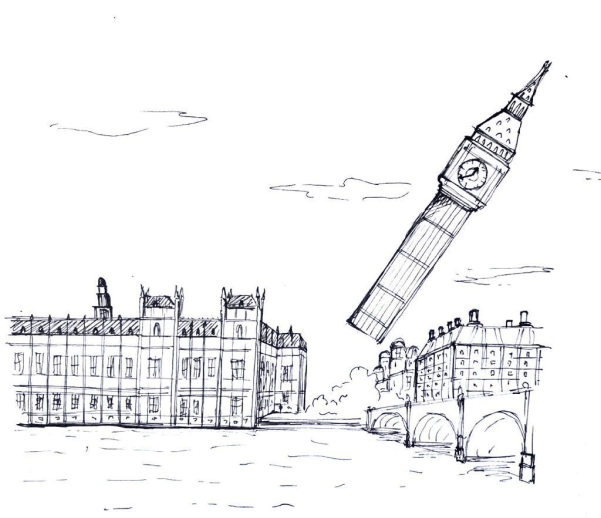

You were approached by the Manchester International Festival, a city with a very wide and very important history of critical thinking, and you suggested doing Big Ben. Time is a…let’s say time is an abstraction, but time is also a property, because there are zones, time zones. And the world is divided longitudinally into these time zones. And you know that the English have the Meridian Line. In the nineteenth century, at the end of the nineteenth century , at a conference in Washington it was decided that zero longitude, the zero meridian, would be in Greenwich. That is, time is measured from the arbitrary line that passes through the Greenwich Observatory which is in the outskirts of London. So for the English, time forms part of the spirit of English culture.

Yes yes, that’s right.

Sure, but you’re moving the meridian to Manchester (laughing). You’re moving the very image of time for the English!

Of course, what I’m interested in is the political relationship in England. They have always been so feudal, so monarchical, yet the working classes grew rapidly in Manchester during the period it was being completely industrialised. And then Margaret Thatcher came along and it all stopped. So moving Big Ben, the sign of London’s power, to Manchester is like giving the power to Manchester, by means of something idealistic. And actually there’s even some humour in it. People see Big Ben lying down, there’s humour there, just like the Obelisco de pan dulce also has humour .

And in a way it’s an anarchic project, being something impossible, something that breaks with consensus in a sense. That generates a sort of space of freedom, but a space of freedom where there are no rules.

There are no rules. Not for anybody.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Studio.

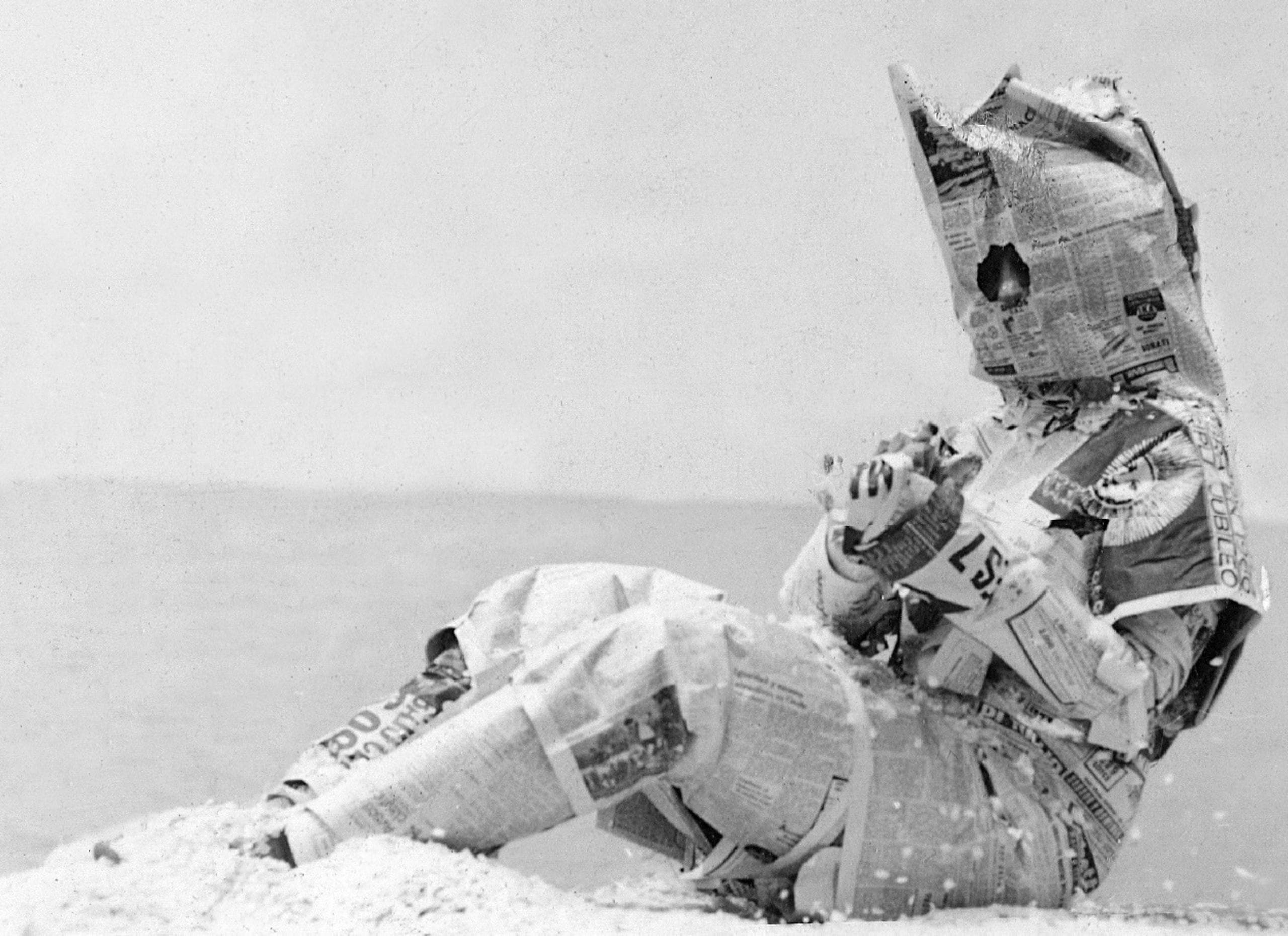

In one sense does it have something to do with your idea of the happening as destruction, like what happened in Paris when you met Christo in the Impasse Ronsin?

I met him there because he was friends with some of the others. We were all poor, so poor, living in Paris. And we would all get together. At that time Paris was the centre of the art world, and I think the centre of the art world now is New York, despite everything. But everyone had their heads turned towards the US, and I started there with ‘action painting’. That’s why I was so interested in doing the Statue of Liberty Lying Down, because so much was happening, with the immigrants, with problems around race, that liberty had to be laid down, because they said to the immigrants, ‘come, come to the US’ and then they locked them up and threw them out. Everything has a political symbol even though I myself don’t create it.

The Statue of Liberty in Hamburgers , 1980.

Drawing by Marta Minujín.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

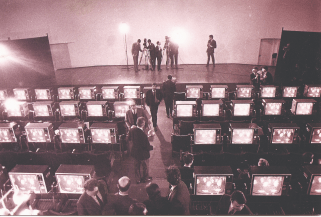

More than a political symbol, I see some kind of unruling impulse in your work. An impulse that isn’t restrained, that doesn’t have any rules… It’s not left or right… It has a kind of force that is unleashed from the energy of the collective will of the people interacting with the work. There’s something that Allan Kaprow said that I wanted to read to you because you were close to Allan, you knew him… he collaborated with you working on Simultaneidad (Simultaneity) in the 1960s…in the year…

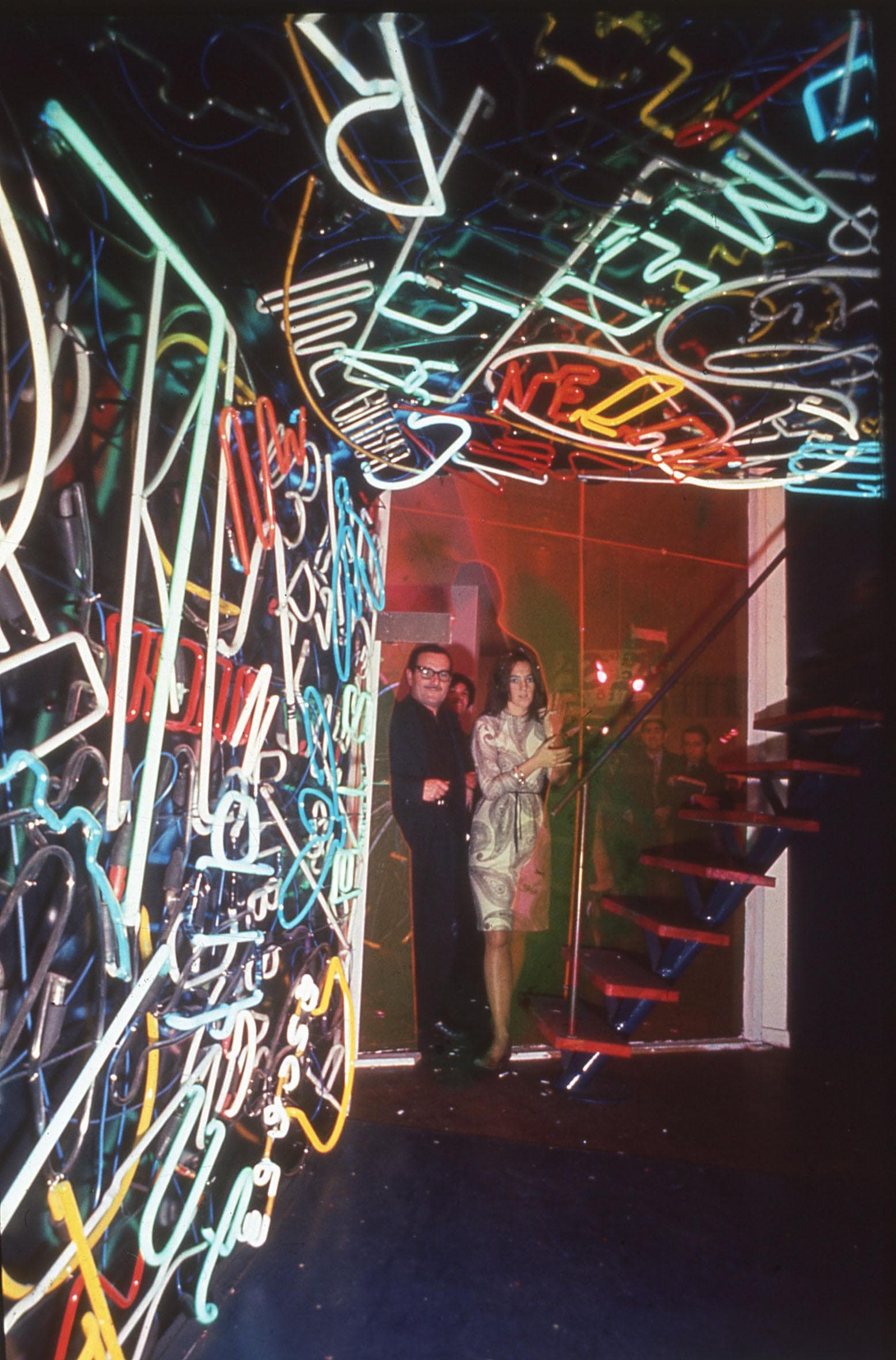

‘66. A three-country-happening and with Vostell, Vostell as well.

in Simultaneity , 1966. Torcuato Di Tella Institute,

Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives

Yes, they are two really famous anarchist-artists, who bring back the tradition of Dada. Allan Kaprow said something that I really like in ‘How to make a Happening’: “Forget all the standard forms of art. Don’t paint pictures, don’t write poetry, don’t build architecture, don’t arrange dances, don’t write plays, don’t compose music, don’t make films, and above all, don’t think you’ll get a happening from putting all of these together. This idea is nothing more than what operas always did, and you see it today in the far-out types of discotheques with their flashing lights and film projections.”

That’s right

It reminds me a lot of the impulse you have that says it’s all of this, but it’s not. It’s not architecture, it’s not an installation, it’s not performance, nor is it a monument.

It’s something. It’s something that provokes a change in thought in other people. Because they see that you can do anything, for example make a Parthenon with 70,000 books, the same size as the Parthenon, a millennium or two millennia afterwards. It’s something irrational, but it’s funny, it’s irrational art, you can’t rationalize it.

to enlarge

You’ve always worked with books that were banned, or with books that contained social thought that was prohibited, and you make them available to people. You’re inviting people to read a literature that was prohibited. That in a way had content that was not widely accepted in some way. Is it you that compiles this literature Marta?

It started with the books that were banned during the military dictatorship in Argentina and simultaneously, twenty years before this, the Nazis had burned all the books that they thought…and here too, the military persecuted publishers, they had to hide if they had published a book. So this is what interested me, how can you censor ideas? In what way can you censor ideas? To break this, it’s also an art to break stigmas, it’s also this.

There’s a kind of necessity to transgress through the history of ideas. One of the other things that Kaprow suggests is that when you talk about culture we’re destroying art. Do you think so too?

No, not at all. I think that art is so fantastic and so free that everyone has to find their own space. People who are going to encounter it are going to encounter it because there are many painters, many sculptors, but few artists. An artist can be someone like Michelangelo, Leonardo, could be Van Gogh, not necessarily because of what they do, but because of who they are, as a person, so it’s an act of magic. It moves away from anything logical.

to enlarge

In the work that you do, do you need to collaborate with different disciplines?

Yes.

To make these pieces which take a lot of energy, you need engineers, you need architects, you need people who operate a camera, you’ve always worked collaboratively How does this collaboration work, what’s the structure of this collaboration? M: Through an energy of fascination, of captivation. That’s why there is a magic to it, because people want to work on the project, they’re mad with excitement to do it and they never forget it.

My question is whether you make something like a film script, or not?

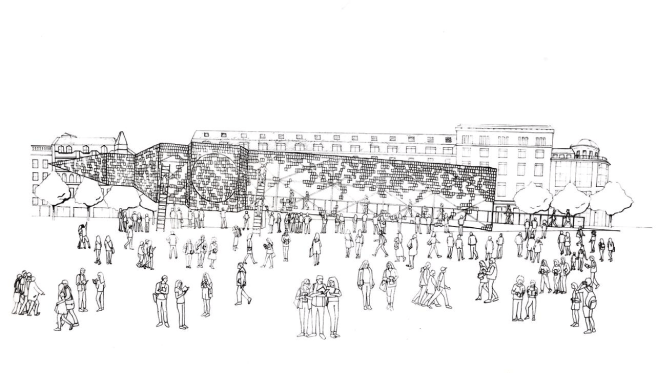

No, no. I don’t do anything, it’s all through talking, it’s all spontaneous. At the moment I have this piece of work, Big Ben Lying Down, but it’s a piece that is being constructed. It’s quite technical because it has a whole metallic structure to it. It’s made of metal scaffolding. You can take it apart easily. If people wanted to make a piece that stays there, they wouldn’t have the money or the space to do it. Imagine making a real Parthenon. No! It would be lying down. No, no, no. For me it’s interesting that it’s fragile. It’s fragile in its’ make up. It can’t last any longer than two or three months. Four months. It’s nothing more than an iron structure. Everyone who works with me, works as an equal. That’s why I say that I always make friends with the people I work with. My friends are the people I am working with. And maybe I’ll never see them again, but it doesn’t matter. It’s like when you make a film and the people there become friends, fall in love, hate each other, whatever. In my happenings, it’s always like that.

You do some very beautiful drawings of this work…you have a series, a collection of drawings of these projects. Are these drawings the structure in some way?

Of course. It’s the fantasy, but they also give an idea of how to create it. Because they are transparent, they are always transparent. To take into account things like the weather - the wind can pass through it. The sun can’t melt it. I have to think about nature too and the place where I make it. So for that reason I need help. If someone says 300 km of wind, then I can’t do it. Things like that happen.

Yes, but I was referring to the fact that your drawings operate like a kind of story in images.

First of all I do the drawings, then people get the idea…it’s complicated. I don’t decide when I’m going to do it. It happens on its own. That’s why it takes so many years and why I haven’t managed to make some monuments because I don’t find the right person who is going to find the place to do it in, who is going to examine the ground, who is going to look at how high things are, so that everything turns out ok. I always need a team of people so that everything turns out well, and other people put up the money. They fund it for prestige, to enjoy themselves.

They are costly projects. Not only the material cost, but in terms of taking a lot of time to put them together.

Definitely.

So, you need a project manager. You need someone who is like the project’s producer. And you also need different people…

In reality I do the producing, because I need to be involved in everything so that the monument is made. I direct it all, live in person, because I also pass on my enthusiasm to the people making it, because often lots of people are working on it for free. They’ve forgotten about money to be there. So, this is good because it’s all a positive thing, these pieces of work are very, very positive. People never forget them. They’re not here on earth any more, but they don’t forget them. Nobody forgot the Obelisco de pan dulce, lying down, they’re never going to forget it. It’s completely conceptual. It goes into people’s souls. It’s a sort of magical thing.

In a way you’re creating a new mythology, as you said. You have to reinvent mythology.

Yes

Another thing that I wanted to ask you Marta is who do you find it easiest to work with? With artists or with critics in these projects?

I don’t work with artists. I don’t work with critics either.

You worked in the past with artists. You had collaborators.

Only with Kaprow and Vostell, and with the artists in La Destrucción (The Destruction)

In Menesunda and in several social environments, for instance, Minucode you worked with different artists.

In happenings, yes.

In La Destrucción …that you did in Paris you asked the artists…

There yes, but that was a long time ago. Now I prefer to work as an individual producer and do things on my own…working with artists… No, I prefer to work with experts, experts in the land, experts in whatever… I love learning from them too. I learn. It’s a very interesting movement because they come together without knowing what for. Nobody does it for money, nobody, not even the people that make the structures. They love being involved in it. For them it’s like an historic moment. I couldn’t do it with another artist because they are as anarchical as me, the other artist. As you said, anarchist.

Well, I don’t think all artists are anarchists, in your work there is mix of a, let’s say, destructive spirit and at the same time you use affective structures. And so it’s like there is always friction in your pieces.

Yes.

Destruction and creation too.

But it’s not destruction, but people… like in Oscar Wilde’s story the Happy Prince, when he says to the swallow, go and take a piece of gold from me to the people who don’t have anything to eat, leave it on the table for them. And the happy prince ends up without any gold. It’s like that. I like that people can take a pan dulce, can take a book, take apart a jigsaw puzzle, they all take part in this dismantling. Which lasts forever. With the books people send each other emails, between themselves, because the books are donated and as there are phone numbers in them, they ring each other. It creates a human connection and many people end up being friends from this project. Friends between themselves. It’s a strange thing, but it’s a very lovely type of art. It’s great.

to enlarge

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives

To me it really stands out that you’re working with time now in Manchester, because the thing that has been dismantled the most during this pandemic, is time. Have you thought about the metaphor of the pandemic as time?

Yes, because I’ve made pieces of work that have to do with one year, work that has to do with other years. The days are always different, but what I do is always the same. I count the hours, like in the piece ‘Pandemic’ I count the hours, 1200 hours. But for me they were moments. Like being in an eternity that didn’t have time. Abstract time.

Monuments don’t have time either, they are timeless. I suppose they cross time. Their meaning changes. The Obelisk was made to commemorate the greatness of…

…and death. They were in mortuaries.

They also remember the grandeur of the people that they commemorate. However, there is an obelisk in the Place de la Concorde in Paris and on the Thames in London. People walk past the obelisks and don’t know what they are.

That they are 3000 years old.

Yes. The one in Paris was a gift from an Ottoman King from Egypt to France. It doesn’t mean what it meant when it was built. It was erected for somewhere that wasn’t Western.

The other story was that they stole it.

What are the projects that you haven’t been able to make from this Monuments series and why couldn’t you do them?

Because nobody was interested in doing them. For example the football made out of dulce de leche. I wanted to do it on a pitch, where the songs from world cups were sung and cranes played with the ball amongst themselves, a gigantic ball of 15 metres, covered in packets of dulce de leche for people to take away. It’s the Argentine myth because people watch the ball in football matches and eat dulce de leche as well. What people eat always interests me. Fish cakes in England, baguettes at the Eiffel Tower, sliced bread in Ireland, food is a very important part of people. What people eat.

Tell me about the piece that you are doing in Manchester.

It is the same size as Big Ben in width, 42metres, the actual one is 96m, reconstructed, made of metal, covered in books that symbolise the conflicts that there have been between Manchester and London. They are books from any era, from the 1700s onwards. It’s going to be very interesting because the people of Manchester are going to read about themselves, and they’re going to have Big Ben. For eighteen days. And they’re going to laugh. Because laughing is a way of communicating. It’s not too difficult. It’s easy to do. For me. For me it’s easy!

Are people going to penetrate Big Ben?

Yes, people are going to be on a slope, and they’re going to walk 42 metres through Big Ben until the end where they will see a film of it leaving London, flying through space and landing in Manchester. Then on the last day, on the Sunday people will take away a book. 20,000 books in this case, that are covering Big Ben.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Studio.

You talk about a rivalry between London and Manchester. I think it’s a rivalry between hegemonic cities, the cities where nearly all the administration of the financial operations and state decisions take place and provincial capitals, which in the case of Manchester was also where the industrial revolution took place, it was a pioneer in the industrial revolution. And it was a pioneer in thinking around decolonisation. So, I think it’s interesting that you’re working with time, because time has been appropriated by the English empire. I’m referring to the Greenwich Meridian again. We calculate time from the Meridian Line. It’s like intellectual property, it’s an arbitrary line, that’s to say, time is an asset that English culture has appropriated.

It’s also got to do with the relativity of time. For example, if you’re in a plane, on a flight and suddenly, in one minute, they say, put on a parachute, (this was an old happening), put on your parachute, because the plane is going to crash. Jump with your parachute on, jump, they jump, but the parachute doesn’t open, they fall on top of another parachute, but they land OK. There are some minutes which seem to last for centuries, like when you’re in danger, and other minutes that are very long. It’s totally relative whether you live a long life, or a short life, like Modigliani, to create an eternity around you. It’s also related to magic. Not to dark magic, but to the magic in the world.

Would you say…because the history of art is generally written in places where there is a strong sense of intellectual property… I also think it’s a time to revisit this dominant temporality…to say we are more advanced or more behind, who determines this? Do you also think that this has to do with the idea of time?

It’s related to the fact that we’re living in a new world. Completely new. At least in the West.

But what I mean is…you did happenings. You went to Paris when you were very young.

20 years old

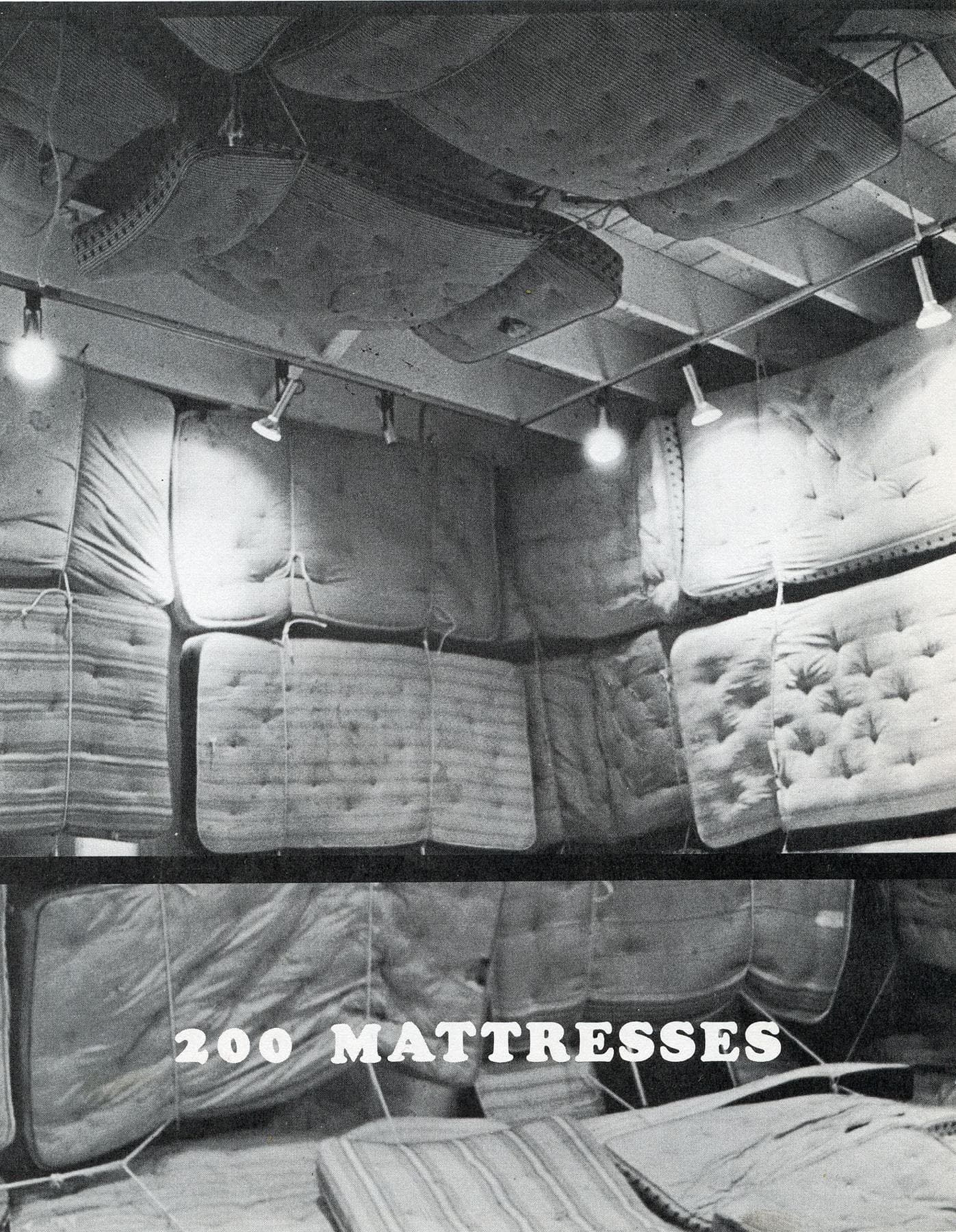

rue Delambre, Paris, France, 1963. Minujín en

su taller de la rue Delambre en París, Francia,

con sus primeros colchones realizados en 1963.

Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives

And you were awarded the Di Tella prize when you were 23 years old

Yes, that’s right.

It was Pierre Restany that voted for you.

and Romero Brest and……

but it was Restany that decided that you won the prize. And he became a great ally of yours and one of your most important sounding boards. He saw that there was a scene developing in Argentina at that time and he looked to you as the person to get involved. He definitely backed you. I read a letter that he sent you when you were in New York in which he describes New York as a very difficult city because an artistic canon had being constructed there since the 1950s. He insisted that you should get involved in the New York underground, which you had got to know a bit when you were in Paris and then you followed that path in New York with emergent video artists and a few countercultural young figures. However, people still talked about how a Latin American artist is always behind in everything and never with the avant-garde. You know what I’m saying.

They’re wrong!

It’s a rethink that’s come about in the past few years. So I think the metaphor of time is also relevant here.

What they think…it’s history that will decide, the future will say who stays and who doesn’t stay in the art world, which is a separate world, a world in a world, just like in literature, or film, we’re all here in the art world.

Totally. Tell me something Marta, out of the people that you’ve known in your life in Paris and New York, where you had an intense time because you were there at the best time for both cities, for Paris and New York. Who were your most important sounding boards in art? Because you had very close friends, like Carolee Schneemann.

In Paris, Alejandra Pizarnik, we were always together and then, Luis Felipe Noé, de la Vega, Alberto Greco, they were all there living together. Those were the Argentine artists and North Americans, Europeans - Christo, the whole Fluxus group, we were all very close. But I also met the philosopher John Paul Sartre, playwright Eugene Ionesco. And in New York as soon as I got there, within a week I met Roy Lichtenstein, George Segal, Claes Oldenburg, all the pop artists. That was fantastic.

You were also good friends with Juan Downey.

And with Carolee Schneeman. Carolee Schneeman is a friend for life. Juan Downey was very funny, because he was the only South American there. And we made a lot of things together like the Cha/Cha/Cha magazine, and some videos that we made, a lot of things.

He collaborated with you in Soft Gallery as well?

There was something going on every day in the Soft Gallery, Ray Johnson came, lots of the Fluxus group came, Charlotte Moorman who played a cello made of ice, naked. Several of the Fluxus group, from the avant-garde, that were in New York. We were all poor, but rich in ideas. We really did have a good time, really enjoyed ourselves.

to enlarge

Harold Rivkin Gallery, Washington DC, USA. Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives

Who do you think was the most transgressive person that enriched you and helped you to mature throughout this, because you matured throughout this period, through the big events that were happening.

Buenos Aires, 1963 Private collection, Buenos Aires, courtesy Del Infinito, Buenos Aires

For me, Alberto Greco out of everyone. But for me world news is very important, I listen to it every day, as if it’s a protagonist, or a good friend, but I listen to news, news, news, good or bad, and that’s how I make things, I invent things from news from all around the world.

It’s like a de-collage, right?

Day after day, after day, day I always know what’s going on. Before I worked with music, classical music, then rock music, then tango and for the past twenty, thirty years when I work I listen to the news.

to enlarge

You’ll end this dialogue saying that your music is the news?

Yes, my music is the news. I want to find out about everything now, about Manchester, about Big Ben, about the people that live in Manchester, about everything that happens in Manchester. It’s going to be my other place in the world. Just like Ireland and all the other places. Because when I make a piece of art, it’s like I’m living on another planet, and I put these nonsensical things on that planet. Nonsense Gabriela, that’s what I like nonsense.

Do you think that news produces images, that they are time?

Not really no, because it disappears so quickly and repeats itself so much that I don’t know if it’s time. It’s a feeling. It’s the effect that it has in people’s heads because it repeats itself, it repeats what’s happened. It does this, it does that, it gets bigger, like a snowball. That’s what the news is like and then it disappears and more comes along. There are very few pieces of news like the man on the moon, or when the Berlin wall fell. They touch the whole world. And that’s what is happening now with the pandemic. The whole world is talking about the pandemic and the vaccines. For example, 80% of conversations, of news is about the pandemic, about the vaccines. Life changed, there is hardly even any time to dream because we’re in a world war. People couldn’t do anything else in the second world war. This is a war against the virus, and I don’t know what level of creativity people can have at the moment. For people that close themselves away, or for people that immerse themselves in the pandemic. But if effects our clothes, effects our thoughts, it effects structures, effects history. The pandemic is like an earthquake.

What would you recommend for a young artist from Manchester. What would you advise them to do?

Find out about everything. To read all the political books that they can get from Big Ben. And to fight for democracy. Always. Democracy of ideas.

What’s the other type of democracy?

The other democracy, is to do with time. Imagine a prisoner in perpetual prison, how does he see time? With a minute hand, because with every day that passes he does the same thing. And the only thing he thinks about is escaping. So there is a very important relationship with time. When society marks it. For example in a war, if it lasts 100 years, or 5 years, or 4 years. If the pandemic lasts 1 year, or 2, or 3 years, until the planet is vaccinated, or maybe more vaccines won’t be needed.

So, there’s an external element that determines the measure of time.

Yes, of course. That’s why it’s better to not have the law of gravity, so that the measure of time isn’t so exact. So we can float. We have to float!

But don’t forget that Rosa Luxemburg, who was in prison for many years, her letters reconstructed time… I think it’s Proust’s ‘Lost Time’.

Yes, you can waste it too. You know it can also be really nice to be able to waste time. Simply by saying the verb, I waste time, you waste time, he wastes time, that’s already wasting time.

Is making art not deep down doing something useless that wastes time?

No, it’s…

Is art useful?

Very useful. Very useful to soften society. Especially if you work with soft things. Mattresses are soft! They’re not rigid.

París, France. Courtesy Marta Minujín Archives.

But you work with metal structures!

But people know that they are not so invincible. Because they have to take them down. So they are vincible.

You have a very generous side Marta, you give people books or food. It’s different.

The art is for them. I don’t like it to be for really educated people that know about art. I prefer for art to reach people who don’t know much about art and who discover art to improve their lives.

I think we’ve talked for a while now, for over an hour.

Well Señora Gabriela, how brilliant that you’ve been here with us talking about the Big Ben project. I hope to see you there. I hope you come to Manchester!

I’d have to cross the Atlantic.

You can cross it, on a raft made by your good self. With your cat.