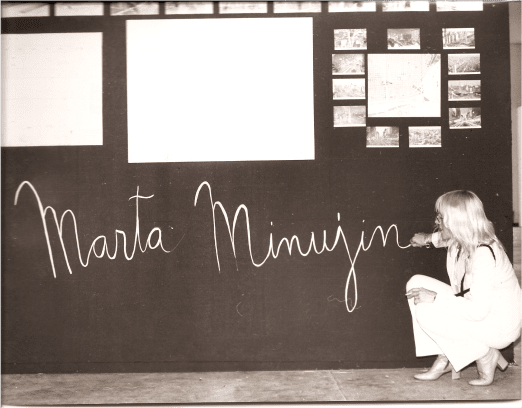

- 01Introduction

By Jorge Glusberg

- 02The Obelisk Lying Down

El Obelisco Acostado, 1978

- 03The Sweet Bread Obelisk

El Obelisco De Pan Dulce, 1979

- 04The James Joyce Tower in Bread

La Torre de Pan de James Joyce, 1980

- 05Carlos Gardel on Fire

Carlos Gardel de fuego, 1981

- 06The Dulce de Leche Football

- 07The Statue of Liberty in Hamburgers

Estatua de la Libertad de Hamburguesas, 1980

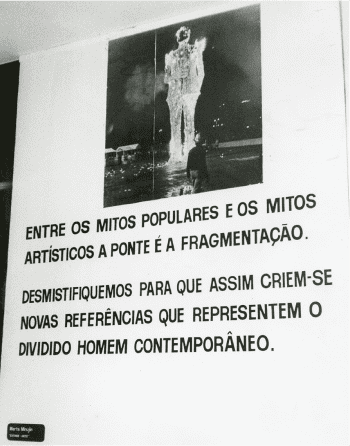

- 08THE FALL OF UNIVERSAL MYTHS 1978 - 2021

La Caida de los Mitos Universales

myths

and

TEXT Jorge Glusberg, 1981

the law

of

gravity

and

of

gravity

A common denominator can be seen to define this work: ostentation and mass participation, a recipient of real things that meet their expectations: panettone, dulce de leche, hamburgers. Is this gratification purely a gastronomic one? No. It is framed within a broader context of a process where the satisfying of appetites has the same meaning as the allusion to the symbols of the daily life of the human being, such as football or the presence of hallowed monuments. In this sense, the de-construction is strongly tied to ecological art. For this reason we refer to her recent works as eco-installations . A distinction ought to be made between an ecology that is specifically natural, and one that is social and cultural, expressed through the massive pieces that Marta Minujín constructs. In this way, an eco-installation would be a piece that takes into account the naturalisation of the cultural, or the imaginary naturalisation of the great mass symbols. An entire conception of man and world is condensed within these fetish-works, which are ultimately nothing other than cultural operators with mass appeal, but at a strictly artistic level.

The active participation of the public constitutes for Marta Minujín the complementary and necessary part of her social work. The social is always manifest in her work, not as a criticism or mockery of collective thought or feeling, but as a socio-contextual interest that contains various nuances: humour, exaltation, criticism, sarcasm, or the metadiscourse of art over reality. Ultimately, it is the recipient who puts the finishing touch on the symbols constructed, granting them their definitive value and their final significance.

versión en español los mitos y la ley de la graveda

This text was originally published by the Centro de Arte y Comunicación (CAyC). CAyc was an arts organization based in Buenos Aires , Argentina , that was instrumental in creating an international arts movement based on the ideas of systems art within conceptual art and was initially conceived as a multidisciplinary workshop to explore the relationship between art, science and social studies; it positioned itself as a space to generate a new wave of experimental art. Artist, curator, critic and businessman Jorge Glusberg served as Director from 1968 until his death in 2012. In the late 1960s and early 1970s CAyC brought together leading thinkers and artists, visiting international figures, the local art community and members of the general public.

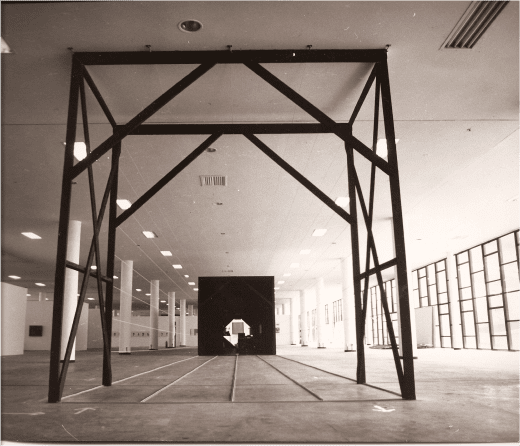

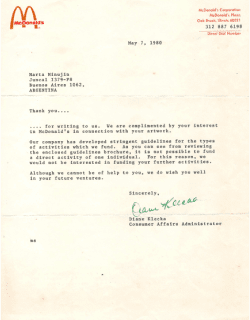

The Obelisk Lying Down

El Obelisco Acostado, 1978

This work has several connotations in its attempt to overturn massive symbols. The first is undoubtedly that of inversion: rendering the vertical horizontal, but at the same time the originality to place on the inside that which is normally outside – the projected images – and the public themselves. And that is where the sense of appropriation comes from, derived from the first: the visitor appropriates the Buenos Aires Obelisk, not by seeing its exterior but by penetrating it, as if the symbol of Buenos Aires par excellence had been turned into a massive artificial uterus. But as in a collective fantasy, a uterus that could contain several people exploring it at the same time and, fundamentally, watching the same thing (the projections), an exterior made up of the dreams and fantasies of the inhabitants of Buenos Aires.

Another sense, this time distinguished from the previous but also connected to them, is the displacement of a myth to other countries. The sanctified exterior thus became the de-sanctified interior by rendering a public monument horizontal. The interior images projected alluded to another type of ritual, this time an artistic and geo-political ritual, in exporting an Argentine cultural myth.

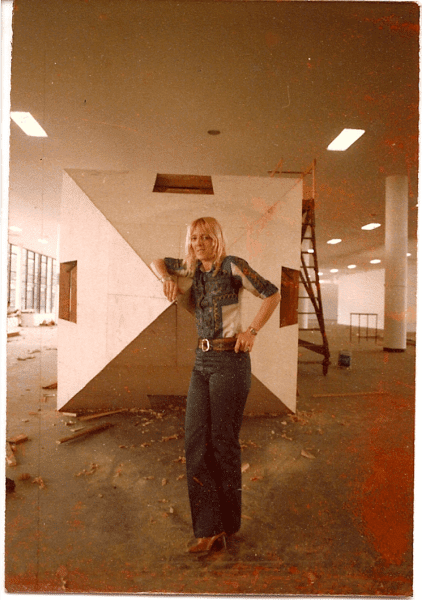

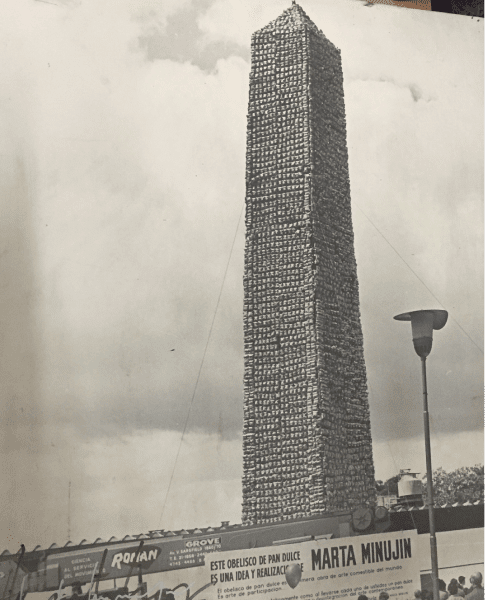

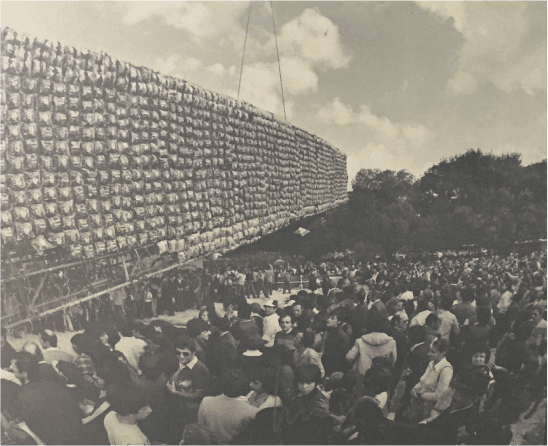

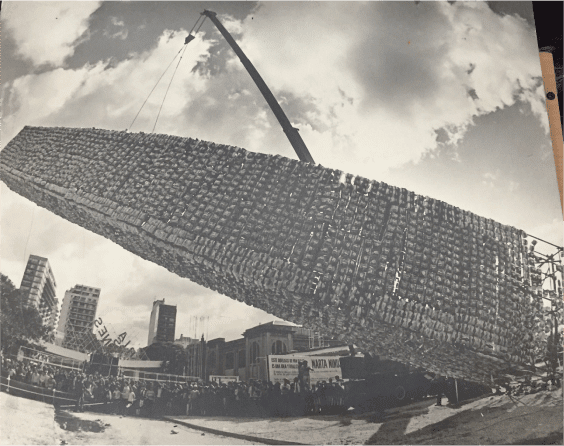

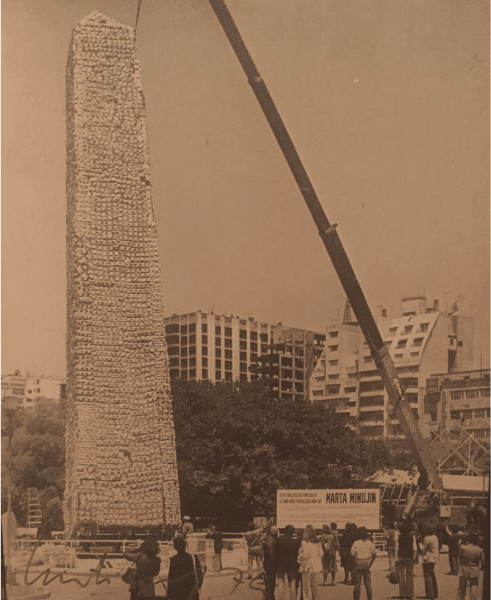

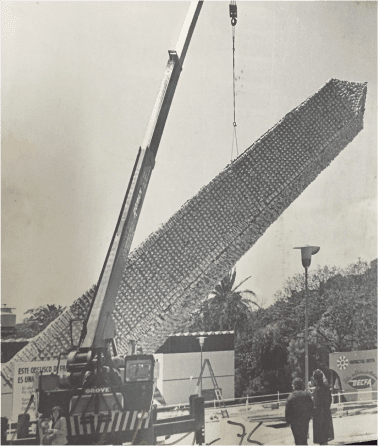

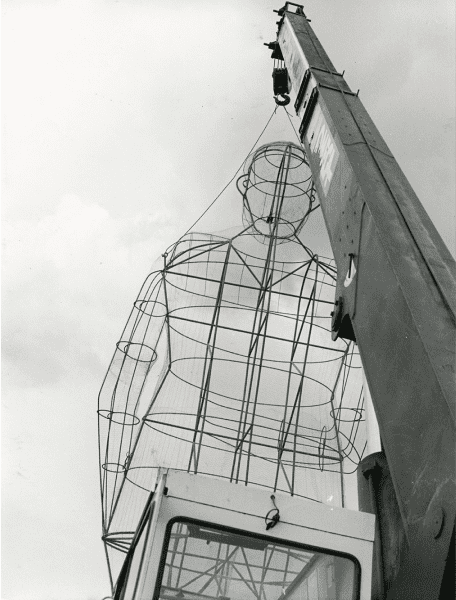

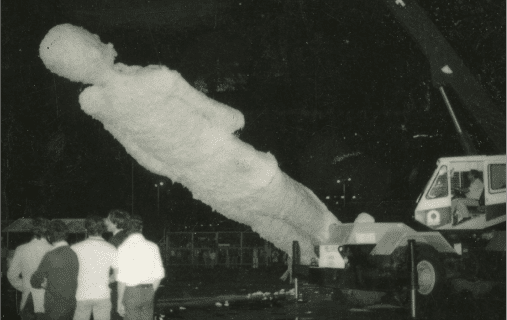

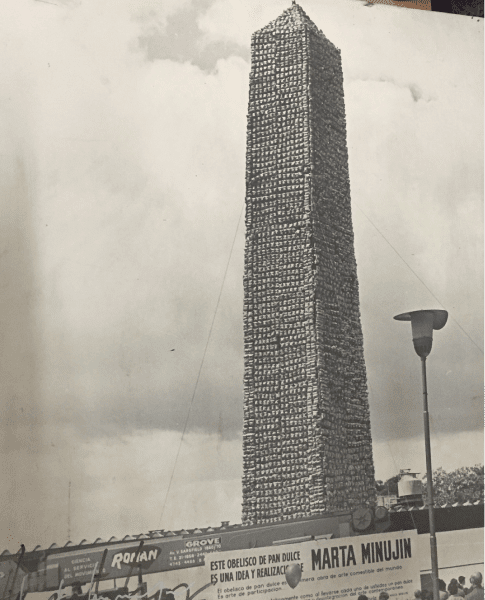

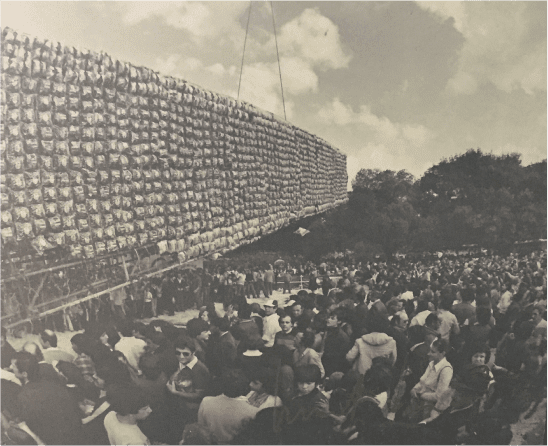

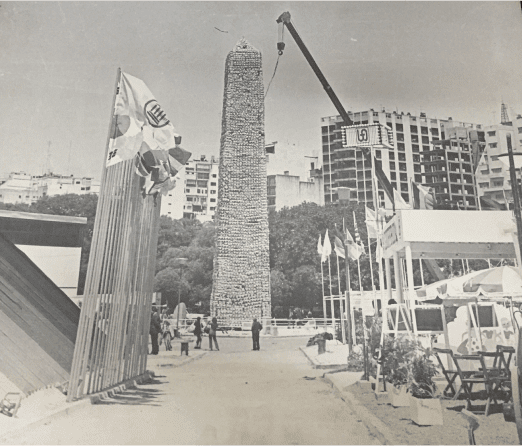

The Sweet Bread Obelisk

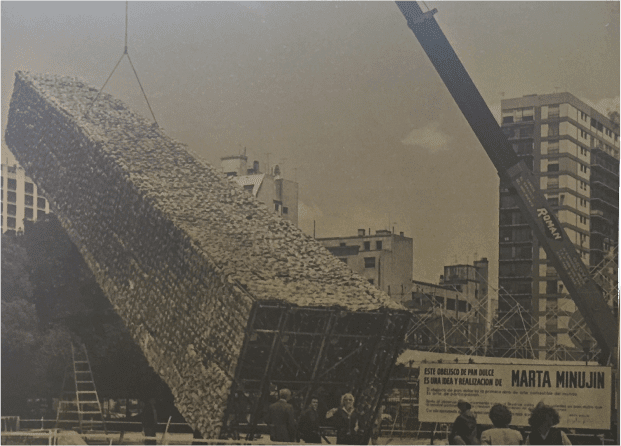

El Obelisco De Pan Dulce, 1979

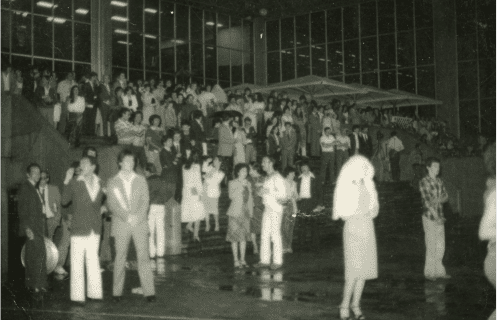

Marta Minujín repurposes the symbology created around these statues for her El Obeliso de Pan Dulce , a 32m-tall metal structure, adorned with 10,000 cakes. Erected on 17 November 1980, a lightweight crane was subsequently used to lay the obelisk down on one of its sides – thanks to a special device placed at the base of the structure – before raising it successively in order to end up placing it on the ground. These mechanical dances were witnessed by large crowds visiting an industrial fair. After having been discovered, fire trucks circled around the obelisk and deployed their ladders, distributing the cakes among the crowds, eventually leaving the structure bare.

This was the first edible structure built by Marta Minujín, and it was to signal the beginning of a period of de-erection of great popular-mythic phalluses, one that was to continue with the James Joyce Tower in Dublin.

The artist offered a concrete response to a common question in Buenos Aires: What is the Obelisk for ? Her response was related to the social function that, through the artistic act, can be incorporated into works that reproduce ancient architectural rituals. But this social function must not be confused with the simple necessity to distribute food. Beyond this, as a veritable symbol of re-production, i.e. of the transformation of public works that are deeply rooted in the collective imagination, the laying horizontal of the mock obelisk , through the aforementioned mechanical procedures, speaks to her proposition to bring down great emblems, to violate the law of gravity.

The artwork stands out for its uniqueness and completeness. These two characteristics were extolled in The Sweet Bread Obelisk . But above all the latter, that is, completeness: from the beginning to the end of the process the public participated actively, even following their surprise and the questions that constituted the social context of the de-erection. If an obelisk is carved up and passed around, it is a shared obelisk. Here we must not forget the verses of Pablo Neruda “…I love the love that is shared in kisses, bed and bread…” from his renowned poem “Farewell”. As a metaphor for the poem, the work of Marta Minujín shared out bread and was devoted to a human deity.

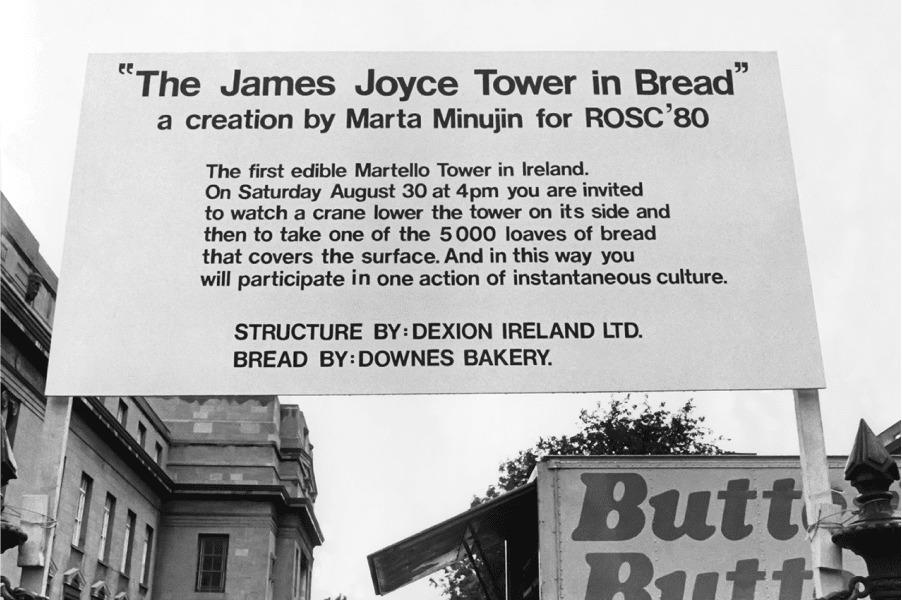

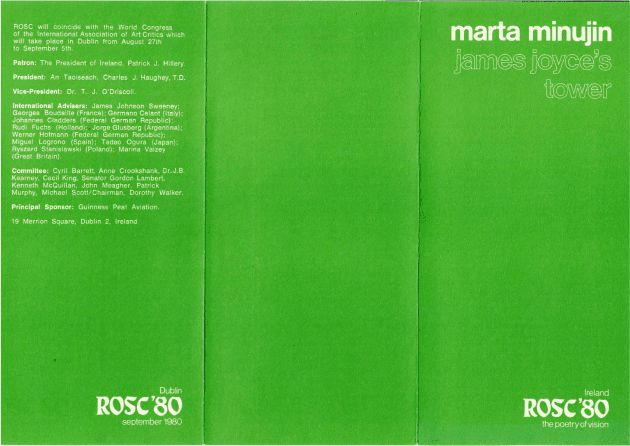

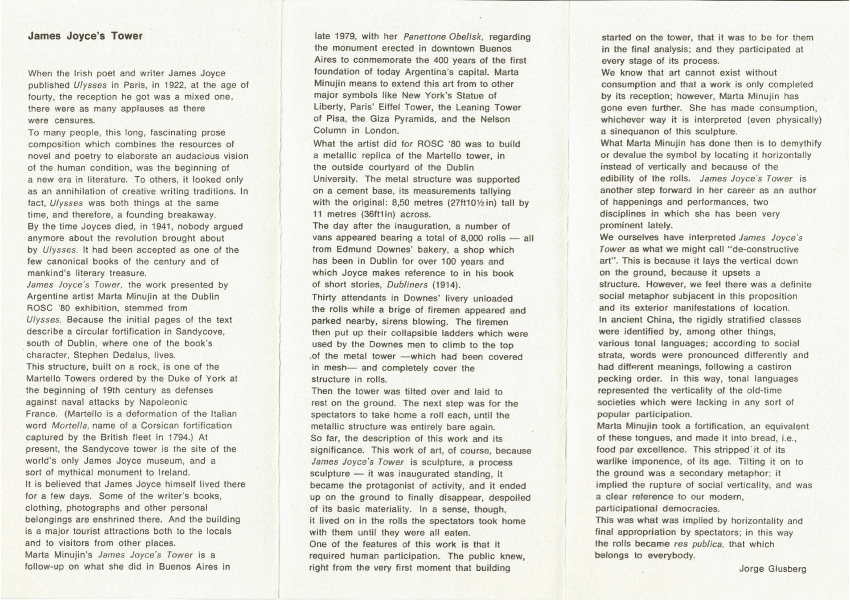

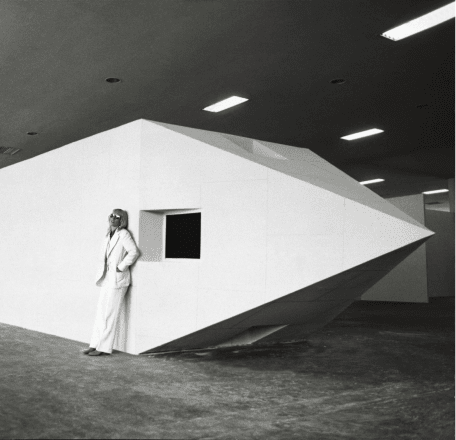

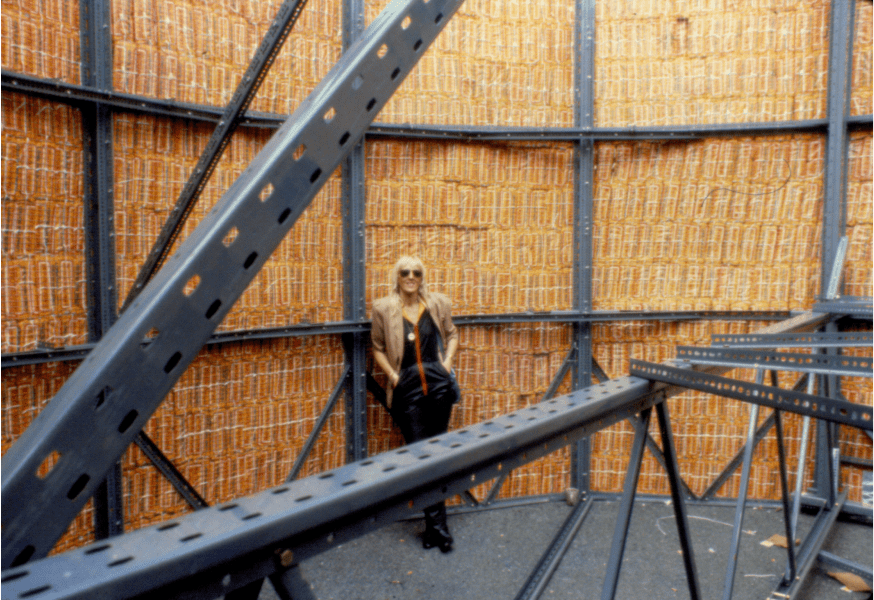

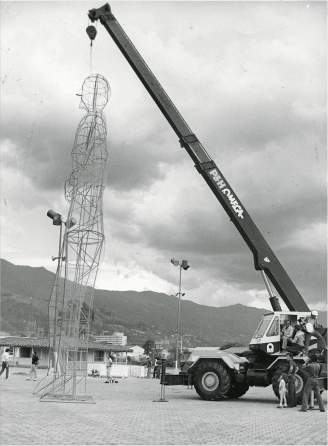

The James Joyce Tower of bread

La Torre de Pan de James Joyce, 1980

Following Joyce’s death, in 1941, no one now ventured to question the revolution ushered in by Ulysses , which had taken its place as one of the canonical achievements of the century and, as such, one of the great works in the literary annals of humanity. Let us recall that in the initial pages of his text, the author describes the circular stronghold of Sandycove, to the south of the Irish capital, which held within its walls one of the book’s lead characters: Stephen Dedalus. Today, the tower of Sandycove is home to the James Joyce Museum and has become a legendary monument for Ireland.

With the James Joyce Tower , Marta Minujín continued the experience she brought to Buenos Aires in late 1979 with her El Obelisco de Pan Dulce , an experience that the artist considered extending to other symbol-monuments such as the Statue of Liberty in New York, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Pyramids of Giza or Nelson’s Column in London. The piece consisted in constructing a replica of the James Joyce Tower in the external patio of Dublin University. This replica featured a metallic structure, lying on a cement base, boasting the same dimensions as the original: 8.50m tall and 11m across. A fleet of trucks brought in 5,000 freshly-baked loaves of bread dispatched by the Edmond Downes bakery, mentioned by Joyce in his book The Dubliners (1914). Thirty people sporting uniforms bearing the Downes logo placed the loaves in the tower, covering the metallic structure. Finally the tower was laid down on the ground with the help of a crane belonging to the Irish fire brigade. At once, the spectators – in a collective commotion where aggression would blend with confusion – ran off with the loaves.

This tower was perhaps the second edible sculpture created, after the Obelisk of 1979. One of the fundamental features of this work was collective participation. Since its erection, the public knew that the tower was made for them. However, their participation was confirmed at every stage of the process. We know that there is no art without consumption; it is in being received that the piece is completed. Marta Minujín went further still, by making – physical – consumption the sine qua non of this process. And so it was that the symbolic was devalued, by making the vertical horizontal, by rendering it edible. The James Joyce Tower is connected to the artist’s transition through happenings and performances , two disciplines in which she has excelled in recent years. The flattening of the Tower renders it de-constructive art , the overthrowing of structures and a clear social metaphor, one that opposes the verticalism of societies in the modern day and in the past that, as in Ancient China, had a language where the stresses used in speech would denote the stratification of social classes.

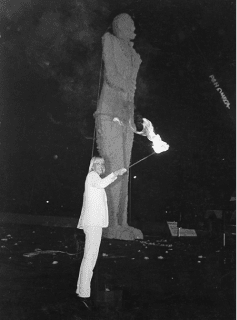

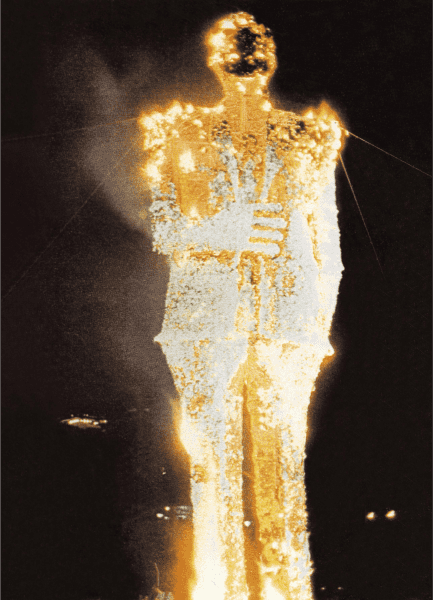

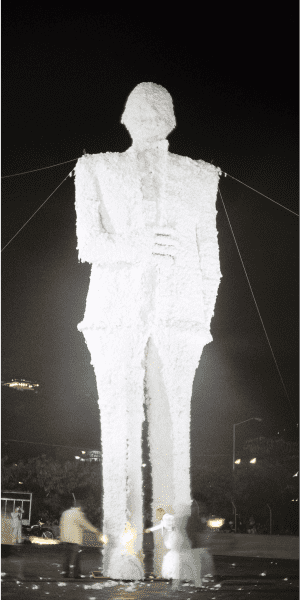

Carlos

Gardel

on Fire

Carlos Gardel de fuego, 1980

The Eiffel Tower, the pyramids of Egypt, Venus de Milo, the Obelisk of Buenos Aires, Brazil’s Sugarloaf Mountain, are some of the popular myths that Marta Minujín has explored and demystified. “These monuments – myths with great popular reach – photographed by thousands of tourists, eternal sites of romantic rendezvous and encounters, constitute the symbol of a place, its most immediate essence; and this is why I am interested in considering the possibility of creating a reflection around its traditional symbology and that of “disrupting them”, converting them into “others…” These words written by the artist reflect her preoccupation along two lines: that of demystifying places, and that of making reflections on emblems that are not buildings, like the football, dulce de leche and, in this case, the figure of the most popular of Argentine singers.

Like the ascending ashes that rose into the sky as the cotton burned, Marta Minujín managed to create an act of mass communication that transformed spectators into the sole recipients of the work. In modifying the physical state of the structure by burning it, the artist managed to break away from the concept of the popular being eternal, and simultaneously offered a ritual image (fire and ashes) that would evoke the tragic moment of the disappearance of this idol. A disappearance that art elevates to the rank of aesthetic recreation of a myth, of a new expressive form that encourages mass participation. Hence the demystification, which is at once a rupture with the eternal in the public consciousness. The evocation of the physical destruction of Carlos Gardel is thus linked to his imperishable nature in the order of collective representations. It was in this dialectics between recovery and destruction that she located the essence of the work, which succeeded in re-creating to show how the physical is perishable and the mythical imperishable.

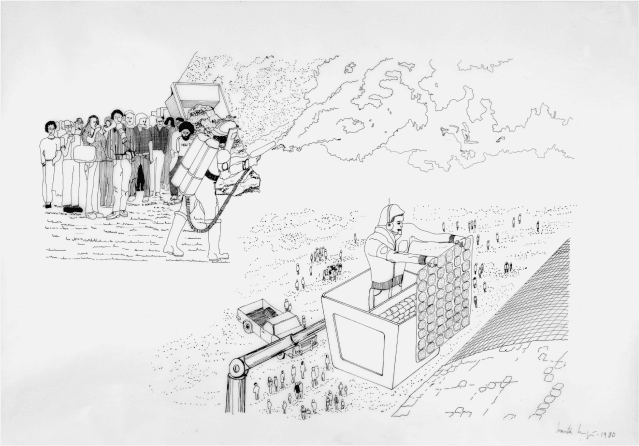

The Dulce de Leche Football

On the conceptual basis that mass participation art consists in touching on those basic resources of human beings, such as feelings, and through these to elicit an emotional and compulsive encounter with the artistic act. The creative process consists, in these cases, in producing an installation in movement, or: the invention of the work, its launch, and its completion or conclusion at the hands of the public.The artist’s intention is to turn the monumental football into a protagonist similar to that which, in a stadium packed with 100,000 people, is watched by 200,000 eyes that follow its every move. This mechanism of substituting a football match with an artistic installation is a clear metaphor for creation supplanting institution; or creation supplanting another kind of creation, which draws public interest every weekend.

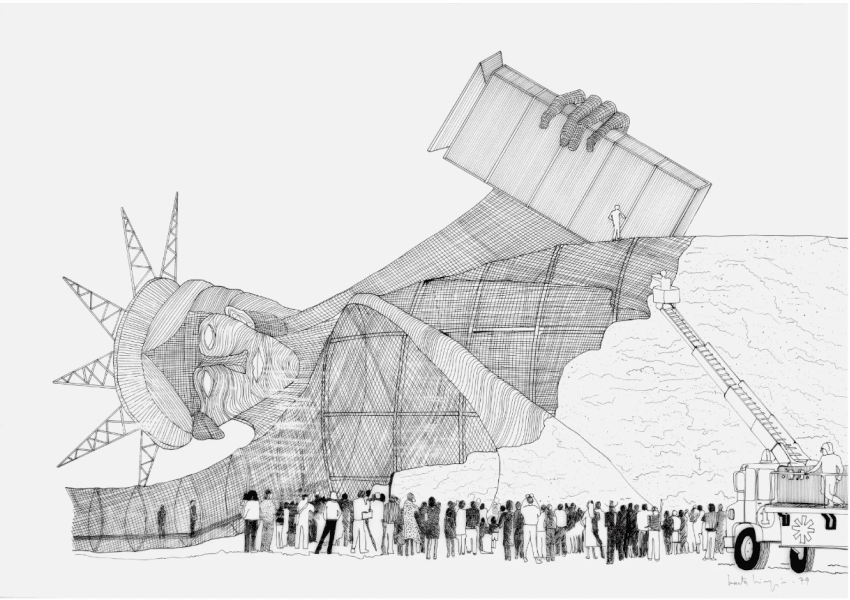

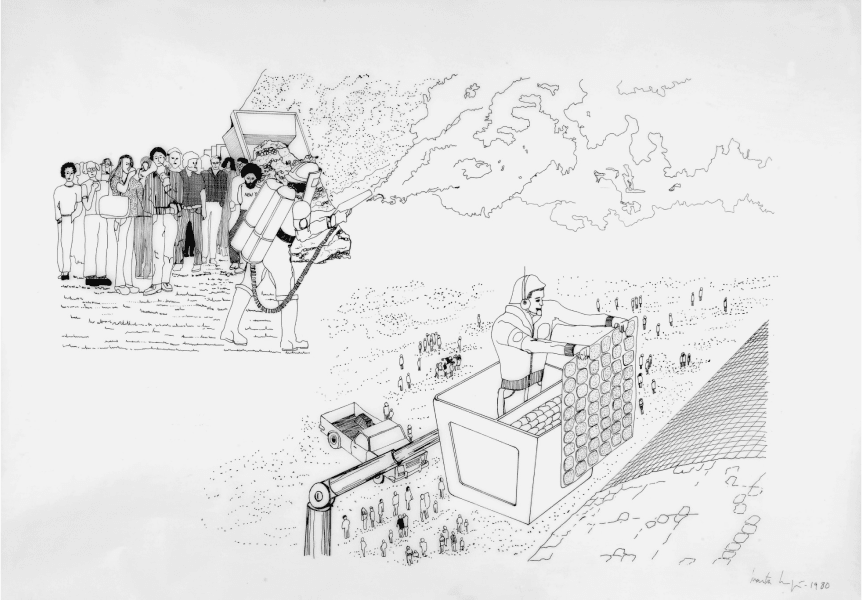

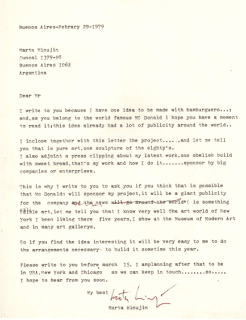

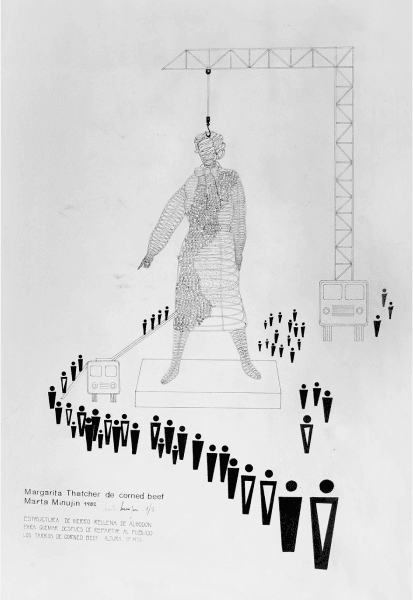

The Statue of Liberty in Hamburgers

Estatua de la Libertad de Hamburguesas, 1980

The idea consists of keeping the statue on display in Battery Park, lit up from the outside and inside. This will enable it to be seen close to the real statue on Ellis Island. At a given point during its exhibition (on the fifteenth day), fire trucks will appear in the morning with their ladders, but they are to be driven by employees of a hamburger company. These employees would coat the statue with a layer of thousands of hamburgers; these would be half-cooked, piled one on top of the other until the iron structure would remain totally covered. Then men wearing asbestos masks and gloves would cook the hamburgers with flamethrowers, toasting them until they become a smoking delicacy. Since this would provide a great public lunch to which everyone would be invited, no one could refrain from gobbling down the hamburgers that covered the Statue of Liberty on just this one occasion.

With this edible installation, Marta Minujín has a twin objective in mind: to bring about a change in the public’s attitude regarding the value ascribed to the monument that the French gifted to the United States, and simultaneously to ensure mass participation through a visual and gustatory stimulus. And she is doing this through a traditionally North American gastronomic symbol (hamburgers), an emblematic accessory, one of the most important symbols in the daily life of the average North American.

The Fall of Universal Myths 1978 - 2021

La Caida de los Mitos Universales

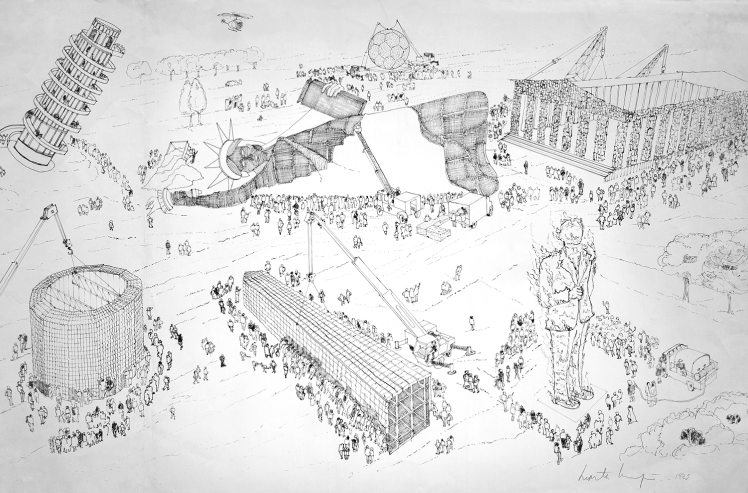

La Caida de Mitos Universales/The Fall of Universal Myths is Marta Minujin’s ongoing series of large-scale artworks begun in 1978:

- 1978 Obelisco Acostado (The Obelisk Lying Down), Bienal Latino-Americana de São Paulo, Brasil.

- 1979 Obelisco De Pan Dulce (The Obelisk in Sweet Bread), Buenos Aires, Argentina

- 1980 The James Joyce Tower in Bread, Dublin, Ireland.

- 1980 Carlos Gardel de Fuego (Carlos Gardel on Fire), 4th Medellin Biennial, Colombia.

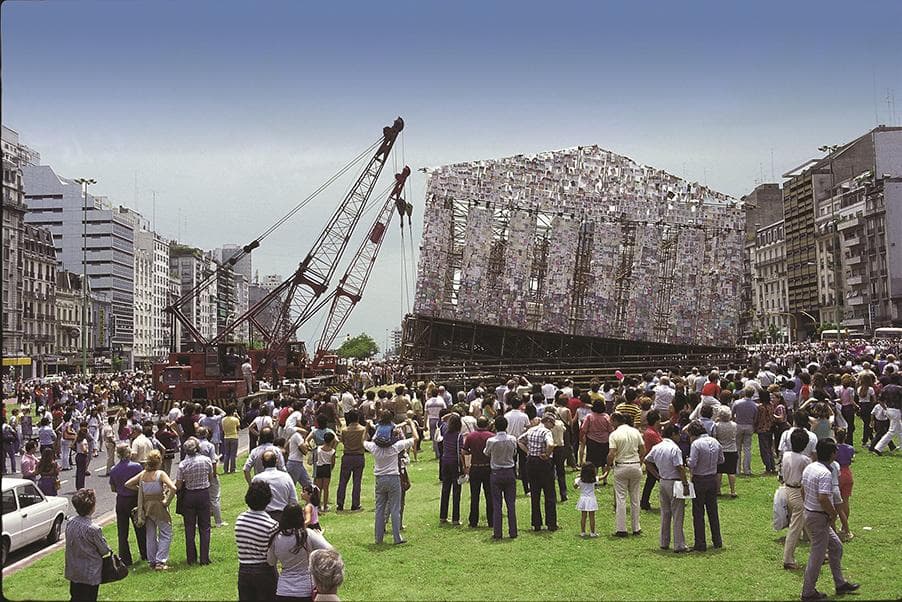

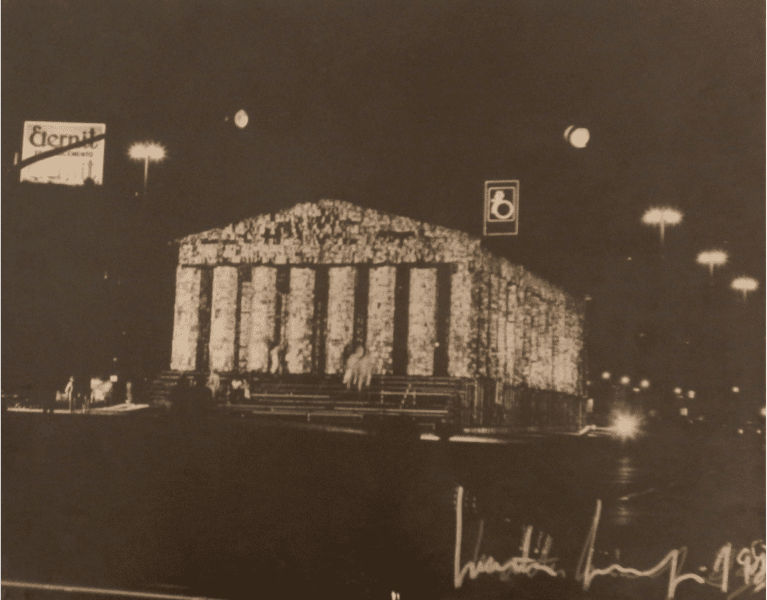

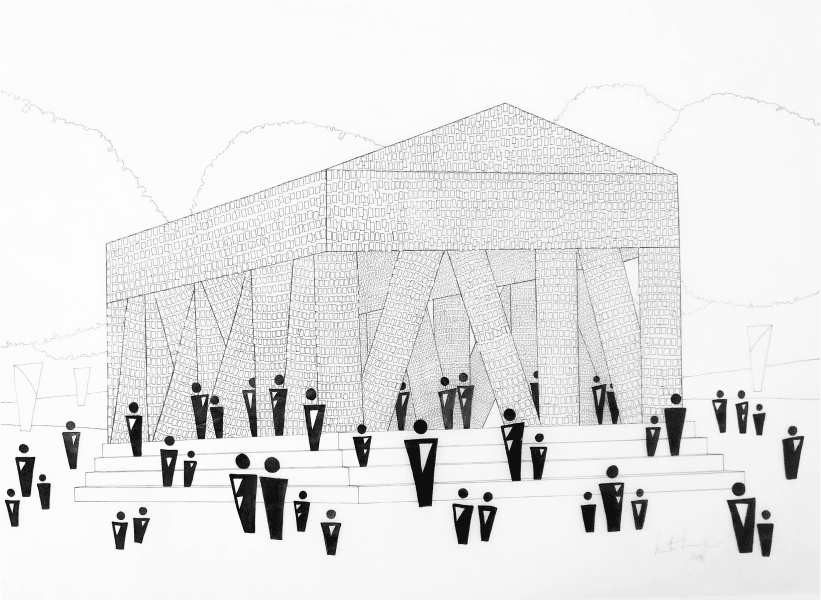

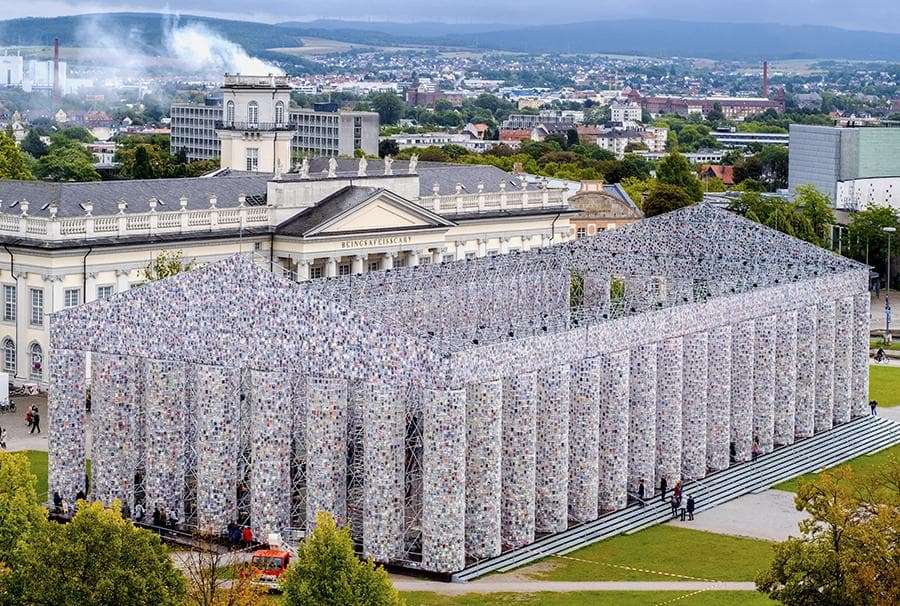

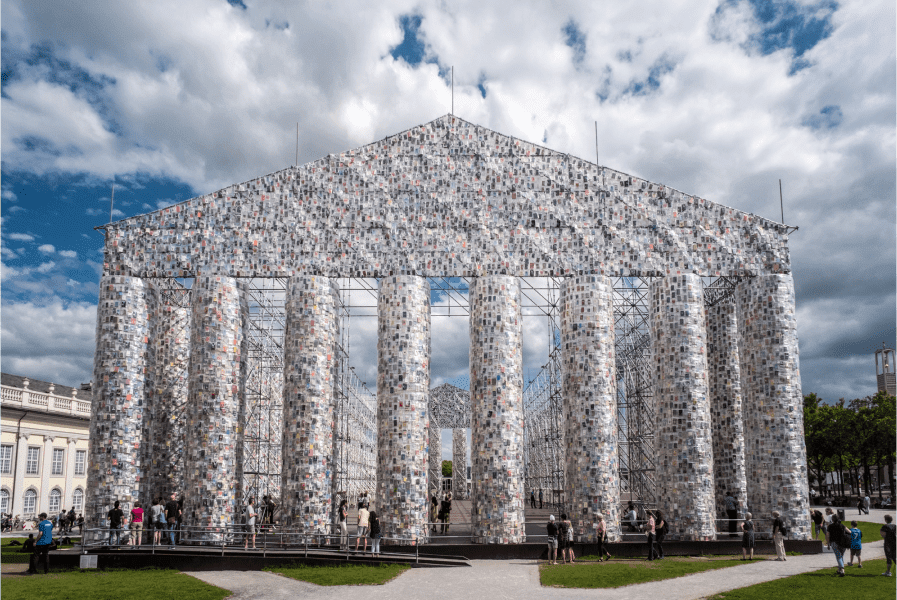

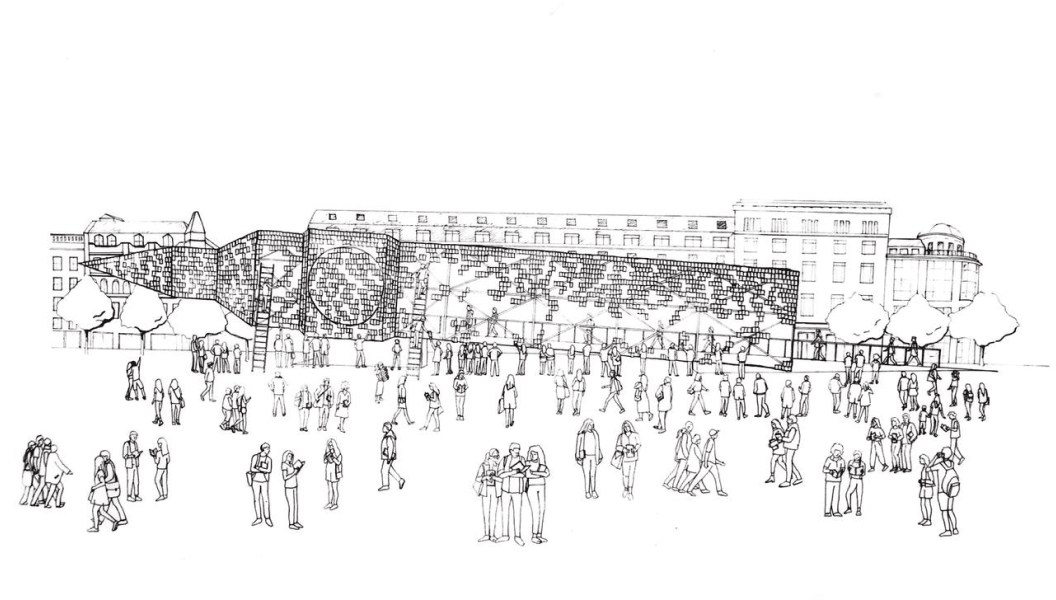

- 1983 El Partenón de Libros/ The Parthenon of Books, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- 2011 Torre de Babel/Babel's Tower, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- 2013 Ágora de la Paz/ Agora of Peace, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- 2014 El Lobo Marino de Alfajores/Sea-wolf of Alfajores, Mar del Plata, Argentina.

- 2017 El Partenón de Libros/ The Parthenon of Books, dOCUMENTA 14, Germany.

- 2021 Big Ben Lying Down With Political Book, Manchester International Festival, UK.